Sofia Gouzouma DVM, Vasileia Angelou DVM, MSc, Christos Koutinas DVM, PhD, Dimitra Psalla DVM, PhD,

Kyriakos Chatzimisios DVM, MSc, MRCVS, Petros Biskas DVM, Lysimachos G. Papazoglou DVM, PhD, MRCVS

Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

MeSH keywords:

dog, pericardial effusion, pericardiectomy, pericarditis

Abstract

A 6-year-old, sexually intact female Brittany spaniel dog was admitted for further investigation and treatment of anorexia and lethargy. Thoracic radiographs revealed a markedly globoid cardiac silhouette, compatible with pericardial effusion. Echocardiographic examination demonstrated a thickened pericardium and a large volume of effusion leading to cardiac tamponade. Cytology of the pericardial effusion obtained by pericardiocentesis was compatible with neutrophilic inflammation. Inoculation of the obtained fluid was negative. A subtotal pericardiectomy was performed under isoflurane anaesthesia. Histopathology of the excised pericardium was compatible with fibrinopurulent pericarditis. The exact cause of pericardial effusion could not be determined. Two years after surgery the dog was in good clinical condition and free of clinical signs. This is a unique case of fibrinopurulent pericarditis in a small breed dog with an unknown aetiology, that was successfully treated with pericardiectomy.

Introduction

Pericardial effusion is defined as an excessive or abnormal collection of fluid in the pericardial space (Monnet 2018). Pericardial effusion in dogs is commonly idiopathic or related to trauma, neoplasia and less commonly associated with bacterial or fungal pericarditis or congestive heart failure (Berg & Wigfield 1984, Aronson & Gregory 1995, Johnson 2004, Heinritz et al. 2005, Shaw & Rush 2007). Pericardial effusion may limit diastolic ventricular filling and when the amount of the effusion is significant or it has appeared in a short period, it will result in cardiac tamponade, which will lead to a decrease in cardiac output, progressive exercise intolerance and/or respiratory distress (Shaw & Rush 2007). Purulent effusion and associated pericarditis consists of accumulation of exudate in the pericardial sac and is a rare cause of pericardial effusion (Fisher & Thompson 1971, Chastain et al. 1974, Price 1986, Fuentes et al. 1991). Diagnostic imaging including radiography and echocardiography along with cytology of pericardial fluid in combination with culture and sensitivity testing are reliable means for the diagnosis of purulent pericardial effusion (Fuentes et al. 1991, Berg & Wingfield 1984). In case of purulent pericarditis pericardiectomy and antimicrobial therapy are required for resolution of clinical signs (Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995). Histopathology of the excised pericardial sac is essential for the confirmation of diagnosis and exclusion of other causative factors (Johnson et al. 2003, Wagner et al. 2006). A few cases concerning purulent pericarditis and effusion in dogs appeared in the literature (Fisher & Thompson 1971, Chastain et al. 1974, Berg & Wigfield 1984, Price 1986, Fuentes et al. 1991). This report describes a case of fibrinopurulent pericarditis in a dog that was managed successfully with subtotal pericardiectomy.

Description

A 6-year-old intact female Brittany spaniel, weighing 10 kg, was referred to the Companion Animal Clinic of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for further investigation and treatment of anorexia and depression. The dog had an outdoor lifestyle and a history of impetigo that was treated in the Unit of Dermatology of our Clinic with oral cefuroxime (20 mg kg-1 every 12 hours for 4 weeks) 3 weeks before admission. On presentation, the dog was lethargic and had a body condition score of 3/5. Clinical examination revealed respiratory distress, hypothermia (rectal temperature 37.5°C), tachycardia (140 min-1), muffled heart sounds on auscultation, pale mucous membranes and a capillary refill time of less than 2 sec.

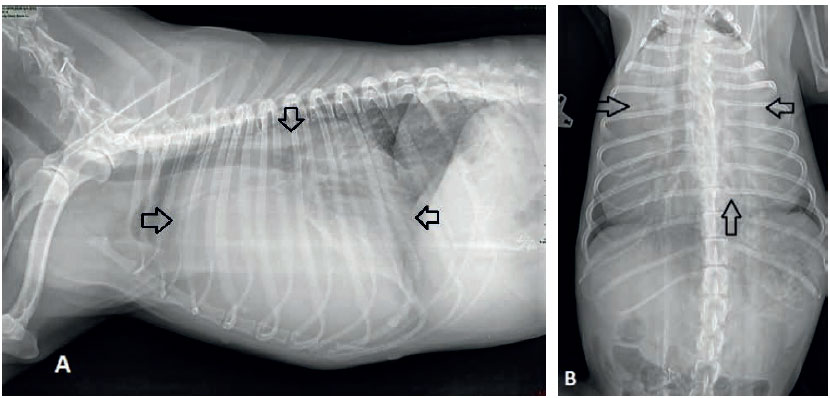

Figure 1. Thoracic radiographs of the dog depicting an enlarged globoid cardiac silhouette (arrows) compatible with pericardial effusion on lateral (A) and ventrodorsal (B) views.

Complete blood count showed mild anaemia (PCV 33.8%; reference range 37.1-55.0%), neutrophilic leukocytosis (31.7 K μL-1; reference range 6.0-17.0 K μL-1), monocytosis (2.7 K μL-1; reference range 0.2-1.1 K μL-1), and serum biochemistry profile revealed hyperglycaemia (143 mg dL-1; reference range 65-118 mg dL-1), hypoalbuminaemia (2.4 g dL-1; reference range 65-118 mg dL-1), elevated alkaline phosphatase (716 U L-1; reference range 32-149 U L-1) and alanine aminotransferase (716 U L-1; reference range 32- 149 U L-1), and slightly increased total bilirubin (0.8 mg dL-1; reference range 0.2-0.6 mg dL-1).

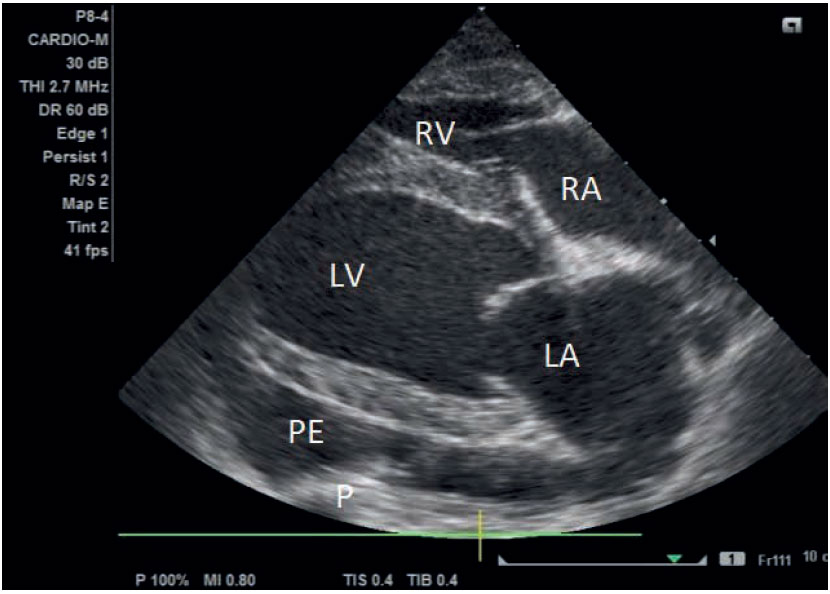

Thoracic radiographs revealed an enlarged globoid cardiac silhouette compatible with pericardial effusion (Figures 1A and 1B). On echocardiographic examination, a large volume of pericardial effusion was detected. A moderate pseudohypertrophy of the left ventricle, collapsed dimensions of all cardiac chambers, and diastolic dysfunction of both right and left ventricles were revealed. Right ventricular and right atrial diastolic function was compromised when subjectively evaluated (collapsed chambers during both systole and diastole). A thick layer of fibrin covered both parietal and mostly visceral pericardium and several linear hyperechoic densities, in the form of tentacles, were noted moving in the pericardial fluid. The pericardial fluid showed homogenous echogenicity. Focal adhesions between parietal and visceral pericardium were detected in two areas near the apex of the heart. No masses were detected at the heart base. A thick layer of fibrin covered both parietal and mostly visceral pericardium and several linear hyperechoic densities, in the form of tentacles, were noted moving in the pericardial fluid. The pericardial fluid showed homogenous echogenicity (Figure 2). Focal adhesions between parietal and visceral pericardium were detected in two areas near the apex of the heart. No masses were detected at the heart base. Systolic arterial blood pressure was 120 mmHg using the HDO method (HDO, S&B, Germany). Abdominal ultrasound revealed an enlarged liver with rounded borders and distended hepatic veins.

Figure 2. Two-dimensional echocardiography of the heart of the dog. LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle; P: pericardium; PE: pericardial effusion.

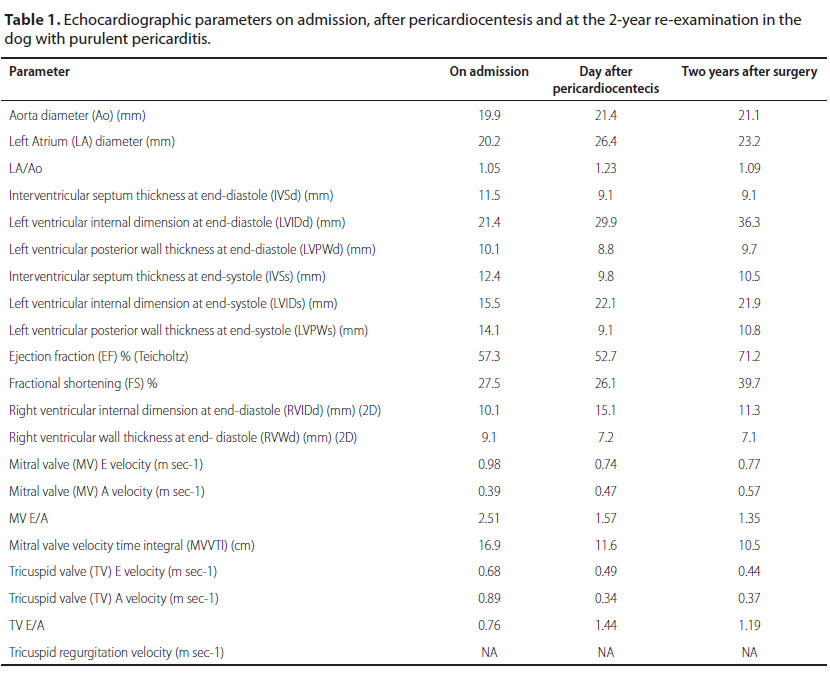

A pericardiocentesis, under echocardiograph ic guidance, was performed, through the 4th intercostal space, with the animal placed in left lateral recumbency. For the procedure, a 16G intravenous over the needle catheter connected to a three-way stop cock valve was used. Approximately 250 ml of cloudy yellowish and highly viscous fluid was drained from the pericardial sac. Echocardiographic examination performed after the pericardiocentesis showed that the amount of fluid in the pericardium was significantly decreased. Cardiac diastolic parameters returned to normal and chamber dimensions increased. At the same time, based on the inflow profile of the tricuspid valve and the normalization of the chamber dimensions, constrictive pericarditis was ruled out. However, right ventricular wall thickness remained increased throughout the study period. Systolic arterial blood pressure was 140-150 mmHg in repeated measurements following perciardiocentesis. Echocardiographic parameters evaluated in our case are presented in Table 1.

NA: not applicable

The collected fluid was submitted for cytology, culture, and sensitivity testing. Cytologic examination revealed the presence of degenerated and non-degenerated neutrophils but no bacterial organisms were identified. Culture yielded no microorganisms or fungi. The sample was inoculated on sheep blood, McConkey and mannitol salt agar for 48 h at 37°C with 100% of oxygen to identify aerobic bacteria. To identify anaerobic bacteria the sample was inoculated on sheep blood and McConkey agar for 48 h at 37°C with 0% oxygen. For fungal identification the sample was inoculated on Sabouraud agar for 15 days at 22°C and 37°C.

An echocardiographic examination performed 3 days after the initial pericardiocentesis revealed the reappearance of large volume of pericardial effusion and relapse of the cardiac tamponade. In order to manage the returning effusion, pericardiectomy was performed.

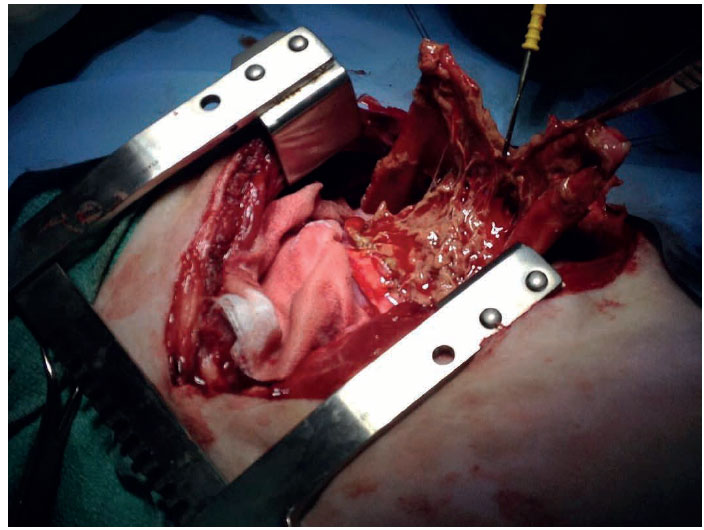

Figure 3. Intraoperative view of the heart of the dog, following pericardial incision. Fibrin is shown to adhere between the two layers of the pericardium. Heart base is on the left and head of the dog is on the top.

The dog was premedicated with intravenous administration of fentanyl (Fentanyl, Janssen, Athens, Greece) (5 μg kg-1) and midazolam (Dormipnol, Viofar, Athens, Greece) (0.5 mg kg-1) intramuscularly (IM). Cefazolin (Vifazolin, Vianex, Athens, Greece) was administered intravenously (IV) at induction (25 mg kg-1) and repeated 90 min later, during surgery. Anaesthesia was induced with propofol (Propofol MCT/ LCT, Fresenius Kabi, Athens, Greece) (2 mg kg-1 IV) and maintained with isoflurane (Isoflurin, Vetpharma Animal Health, Barcelona, Spain) in oxygen under intermittent positive pressure ventilation. A subtotal pericardiectomy through a right 4th intercostal thoracotomy was performed. Upon entering the pericardial sac, the pericardial effusion was suctioned. Following pericardiectomy, an attempt was made to remove as much as possible fibrinous tissue attached to the visceral pericardium (Figure 3). The thoracic cavity was lavaged with copious amounts of warm sterile normal saline and an intercostal block was made using bupivacaine hydrochloride (Bupivacaine, Mylan, Cyprus) (1 mg kg-1) to provide postoperative analgesia. A chest drain was placed through the 6th intercostal space; thoracotomy closure was performed with simple interrupted 2/0 polydioxanone sutures for the thoracic wall and continuous 2/0 polydioxanone sutures in a continuous pattern for muscular apposition and subcutaneous closure. Skin was closed with a Ford interlocking suture pattern using 3/0 polyamide suture. The dog made an uneventful recovery from anaesthesia and received fentanyl (0.025 μg kg-1 min-1 IV) for the first 24 hours. Bupivacaine hydrochloride (1 mg kg-1) was infused through the chest drain every 12 hours for the first 24 hours. Robenacoxib (Onsior, Novartis Animal Health, Frimley, United Kingdom) (2 mg kg-1) was given IM. The dog received meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Ingelheim/Rhein, Germany) (0.2 mg kg-1 IV once per day) and tramadol (Tramal, Vianex, Athens, Greece) (3 mg/kg IV every 8 hours) starting the day after surgery for 5 days. The dog also was treated with a combination of enrofloxacin (Baytril, Bayer Animal Health GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany) (10 mg kg-1 once per day IV) and clindamycin (Clindamycin, Fresenius Kabi, Athens, Greece) (11 mg kg-1 IV every 12 hours) for 8 days. Fluid aspirated through the chest drain was haemorrhagic for 48 hours, becoming serosanguinous 3 days after surgery. The chest drain was removed 5 days after surgery and the dog was discharged 3 days later, with instructions to continue oral antibiotic therapy for at least 4 weeks.

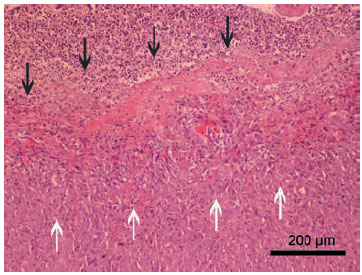

Figure 4. Purulent exudate (black arrows) covers the granulation tissue

(white arrows), which has caused thickening of the pericardium. Staining

with haematoxylin-eosin.

Histopathologic examination of the excised tissue confirmed severe pericardial thickening. The inner layers were necrotic and replaced by fibrin, cellular and nuclear debris and degenerated leukocytes (mainly neutrophils). Necrotic layers were covered by granulation tissue characterized by interlacing fascicles of activated fibroblasts and newly formed capillary vessels. Multifocally and more intensely on the interface between areas of necrosis and granulation tissue there was infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic examination, diagnosis of fibrinopurulent pericarditis without any signs of malignancy was made. Cultures obtained from the pericardial tissue were negative for bacterial organisms.

The dog was re-examined 3 months and 2 years after surgery and found to be in good clinical condition. Echocardiographic parameters two years after surgery remained unchanged. Due to lack of tricuspid or pulmonary valve regurgitation, Doppler estimation of pulmonary arterial pressure was not applicable. Systolic arterial pressure was 140-150 mmHg in the follow-up consult using the HDO method.

Discussion

Purulent pericardial effusion is an uncommon cardiac condition accounting for 2.4% of the dogs presented with pericardial effusion (Berg & Wingfield 1984). Large breed dogs are commonly affected, but small breeds are also reported (Fisher & Thompson 1971, Chastain et al. 1974, Berg & Wingfield 1984, Price 1986, Fuentes et al. 1991). In this case, the dog was a Brittany spaniel.

Clinical signs and physical examination findings reported in the dog of our study were compatible with those reported by others (Berg & Wingfield 1984, Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995, Johnson et al. 2004). Most of the clinical findings could be associated with the pericardial effusion. Severity of clinical signs are related to the rate and magnitude of fluid collection (Aronson & Gregory 1995). Presence of a large volume of fluid into the pericardial sac leads to cardiac tamponade and cardiac function will be affected in case of cardiac compression (Monnet 2018). In the present case, the presence of cardiac tamponade was clinically manifested by tachycardia and muffled heart sounds. Hepatic congestion and elevated liver enzymes were secondary to the onset of right heart failure because of cardiac tamponade (Wagner et al. 2006).

Anaemia reported in the dog of the present study was attributed to chronic disease (Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995), whereas hypoalbuminaemia has been associated with congestive heart failure or effusions into body cavities, among other causes, and is not specific for pericardial effusion (Johnson et al. 2004).

Echocardiography allows detection of pericardial effusion with high sensitivity and specificity (Berg & Wingfield 1984, Aronson & Gregory 1995, Johnson et al. 2004). In our case, echocardiography revealed a large volume of pericardial effusion with evidence of pericardial thickening, cardiac tamponade, several tentacle-like, linear and irregular hyperechoic densities were demonstrated in the pericardial sac, compatible with fibrinopurulent pericarditis when compared to intraoperative and histopathologic findings (Johnson et al. 2004, Wagner et al. 2006).

Diagnostic utility of pericardial effusion cytology was 7.7% in a recent study (Cagle et al. 2014). However, cytologic analysis of the pericardial fluid in case of purulent effusion may demonstrate degenerated neutrophils and bacterial organisms (Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995). Definite diagnosis of purulent pericarditis is established by cytology of the pericardial fluid, culture and sensitivity of the fluid and pericardium and histopathology of the excised pericardium (Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995). In our study, cytologic analysis of the pericardial fluid showed degenerated neutrophils; however, no bacteria were identified. Cultures taken from the pericardial fluid and pericardium were also negative for bacterial organisms. It is believed that prior antimicrobial treatment with cephalexin for pyoderma could be the reason cytology and cultures were negative for bacterial organisms in the case presented here (Beco et al. 2013).

Documented causes of purulent pericardial effusions in dogs may be caused by migrating foreign bodies, gunshot injuries, bite wounds or micro-organisms (Fisher & Thompson 1971, Chastain et al. 1974, Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995). In a study of 5 dogs with infectious pericarditis, grass awns were removed in only 2 of the dogs (Aronson & Gregory 1995). The cause of purulent pericardial effusion and pericarditis could not be identified in the dog of the present study. However, the possibility of a grass awn migration cannot be ruled out as our dog lived outdoors in an area where grass awns are commonly identified. Mixed microbial infections are commonly cultured from dogs with infectious pericardial effusions associated with foreign bodies (Aronson & Gregory 1995).

Pericardial effusion in dogs can be successfully managed with pericardiocentesis or pericardiectomy (Berg & Wingfield 1984, Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995, Aronsohn & Carpenter 1999, Johnson et al. 2004). Subtotal pericardiectomy decreases the pericardial surface area, diminishes fluid production and increases the absorptive surface area by allowing fluid to accumulate into the pleural cavity (Monnet 2018). Subtotal pericardiectomy also allows for obtaining tissue samples for histopathology, culture and sensitivity tests (Monnet 2018). In our study we performed intercostal thoracotomy subtotal pericardiectomy, ventral to the phrenic nerves, to remove septic pericardium and fibrin adhered to the parietal pericardium, search for a foreign body and obtain tissues for culture and sensitivity testing. Prior antibiotic treatment for skin disease, that was recently discontinued in our dog, may have resulted in false-negative cytology and culture of the pericardial fluid and pericardium, respectively (Beco et al. 2013, Mastora et al. 2018, Singh & Weese 2018). In the present study, the diagnosis of purulent pericarditis, with no evidence of bacteria, was based on histopathologic examination of the excised pericardium, which was consistent with findings compatible with severe fibrinopurulent pericarditis (Fuentes et al. 1991, Aronson & Gregory 1995, Johnson et al. 2003). In contrast, histopathologic examination of idiopathic pericarditis is characterized by pericardial thickening, fibrosis, haemorrhage and mild inflammatory reaction (Aronsohn & Carpenter 1999). Despite the negative cultures, we decided to proceed with empirical antimicrobial treatment, based on severe inflammatory reaction, degenerated leucocytes, necrosis and fibrin deposition as shown in our histopathology findings and findings reported by others (Aronson & Gregory 1995). Subtotal pericardiectomy and antimicrobial treatment achieved resolution of clinical signs after a follow-up period of 2 years.

Unique features of the case presented here include a fibrinopurulent pericarditis in a small breed dog with an unknown causative factor. Cardiac ultrasound revealed pericardial effusion with several tentacle-like, linear and irregular hyperechoic densities compatible with fibrin. No bacteria were isolated from the pericardial fluid possibly due to previous antibiotic treatment for pyoderma. The dog underwent a subtotal pericardiectomy and empirical antibiotic treatment and found to be free of clinical signs of cardiac disease after a long follow-up time of 2 years. Histopathologic examination of the excised pericardium confirmed the diagnosis of fibrinopurulent pericarditis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aronsohn MG, Carpenter JL (1999) Surgical treatment of idiopathic pericardial effusion in the dog: 25 cases (1978-1993). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 35, 521-525.

- Aronson L, Gregory C (1995). Infectious pericardial effusion in five dogs. Vet Surg 24, 402-407.

- Beco L, Guaguere E, Mendez CL, et al. (2013) Suggested guidelines for using antimicrobilas in bacterial skin infections (1): diagnosis based on clinical presentation, cytology and culture. Vet Rec 172, 72-78.

- Berg RJ, Wingfield W (1984) Pericardial effusion in the dog: a review of 42 cases, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 20, 721-730.

- Cagle L, Epstein S, Owens S, et al. (2014) Diagnostic yield of cytologic analysis of pericardial effusion in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 28, 66-71.

- Chastain CB, Greve JH, Riedesel DH (1974) Pericardial effusion from granulomatous pleuritic and pericarditis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 164, 1201-1202.

- Fisher EW, Thompson H (1971) Congestive cardiac failure as a result of tuberculous pericarditis. J Small Anim Pract 12, 629-632.

- Fuentes VL, Long KJ, Darke PGG et al. (1991) Purulent pericarditis in a puppy. J Small Anim Pract 32, 585-588.

- Heinritz CK, Gilson SD, Soderstrom MJ et al. (2005) Subtotal pericardiectomy and epicardial excision for treatment of coccidioidomycosis- induced effusive- constrictive pericarditis in dogs; 17 cases (1999-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 227, 435-440.

- Johnson S J M, Martin M, Stidworthy M (2003) Septic fibrinous pericarditis in a cocker spaniel. J Small Anim Pract 44, 117-120.

- Johnson SM, Martin M, Binns S et al. (2004) A retrospective study of clinical findings, treatment and outcome in 143 dogs with pericardial effusion. J Small Anim Pract 45, 546-552.

- Mastora H, Papazoglou LG, Patsikas M, et al. (2018) Retroperitoneal abscess associated with a migrating grass awn in a cat: treatment with omentalization and grass awn removal. Topics Compan Anim Med 33, 97-99.

- Monnet E (2018) Pericardial surgery. In: Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. Johnston SA, Tobias KM (2nd edn). Elsevier: St Louis, pp. 2084-2092.

- Price PM (1986) What is your diagnosis (mineralizing pericarditis)? J Am Vet Med Assoc 188, 1447-1448.

- Shaw SP, Rush JE (2007) Canine pericardial effusion: pathophysiology and cause. Compend Contin Educ Vet 29, 400-403.

- Singh A, Weese JS. Wound infections and antimicrobial use. In: Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. Johnston SA, Tobias KM (2nd edn). Elsevier: St Louis, pp. 148-155.

- Wagner A, MacGregor J, Sharkey L et al. (2006) Septic pericarditis in a Yorkshire terrier. J Vet Emerg Crit Care, 16, 136-140.

Corresponding author:

Lysimachos Papazoglou

e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.