> Abstract

Protein-losing Enteropathy (PLE) stems from multiple causes and it manifests as malabsorption syndrome. In the present report two canine cases of PLE are described, due to eosinophilic, lymphoplasmacytic enteritis and intestinal lymphangiectasia. History and physical examination findings included chronic intermittent diarrhoea, weight loss, subcutaneous oedema and ascites. Biochemistry revealed hypoalbuminaemia and hypoproteinaemia. Both cases underwent exploratory laparotomy in order for multiple histopathology samples from the small intestine to be collected. Treatment was administered in both cases for the primary cause. Response to treatment was satisfactory, despite complications due to long-term administration of medications. These specific cases are of particular interest due to comparatively long-term survival times and satisfactory clinical responses following initiation of treatment, despite the poor prognosis usually reported in the literature.

> Introduction

Protein loss may occur through various pathological conditions, mainly due to chronic enteropathy, nephropathy (glomerulonephritis), and hepatic failure. PLE is a syndrome, which includes every disorder or pathological condition of the intestine that may cause disproportionately greater than normal protein loss through the intestinal lumen.1 Chronic intestinal disorders comprise the most important cause of chronic protein loss, manifesting as a syndrome of maldigestion/malabsorption.2 Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI), apart from leading to secondary Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) or to infiltration of the intestinal mucosa by lymphocytes and plasmacytes, may also result in the development of maldigestion at first and malabsorption later. Furthermore, idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), antibiotic responsive enteropathy, chronic parasitism (Giardia spp., Isospora spp, Cryptosporidium spp., Histoplasma spp.), breed-related enteropathies (Basenji, Shar Pei, German shepherd), villous atrophy, diffuse neoplasms of the small intestine (intestinal lymphoma etc.), short bowel syndrome, brush border enzyme deficiency and lymphangiectasia (primary or secondary) may lead to malabsorption syndrome.2

Malabsorption syndrome usually manifests as chronic diarrhea and significant weight loss. The main laboratory findings include hypoalbuminaemia-hypoproteinaemia.3 When the most common causes of chronic enteropathy are excluded, differential diagnosis includes IBD and lymphangiectasia. Lymphoplasmacytic enteritis is the most common cause of IBD in dogs, the origins of which remain unclear, even though activation of the immune response due to impaired cell-mediated immunoregulatory mechanisms is considered possible.2 Eosinophilic enteritis, though more common in cats, can be a cause for IBD in dogs as well. Lymphangiectasia can be congenital or acquired (lymphoplasmacytic enteritis, eosinophilic enteritis) and it is defined by lymph stasis in the lymphatic vessels of the intestinal submucosa and the villi.1

In lymphangiectasia there is distension of the intestinal lymphatic vessels and lymph stasis in the latter, resulting in generalised lymph stasis and increase in intraluminal lymphatic pressure, extending to the lymphatic vessels of the mesentery.1-2 Therefore, lymph spills into the intestinal lumen by lymphatic rupture, due to the increased pressure in lymphatic vessels, and by extravasation, resulting in loss of lymph components, including protein, lymphocytes and lipids (chylomicrons), resulting in severe hypoproteinaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and lymphopenia. 3-4 Part of the protein released in the intestinal lumen may be reabsorbed. However, the main portion is discarded through the faeces.1,4

The present report describes a pair of canine cases with PLE, focussing on the diagnosis and management.

> Case 1

A 6.5-year-old, female spayed mongrel, weighing 13.4 kg, was admitted to the Companion Animal Clinic (CAC), of the A.U.Th. due to selective appetite and/or anorexia and chronic intermittent diarrhea. This was an indoor dog, incompletely vaccinated and dewormed. According to the history, the appearance of the stool was liquid brown since July of 2015 and there was mild abdominal distension. The dog was admitted to a private practitioner, who administered a clinical diet for gastrointestinal support (Hill’s Prescription Diet Canine i/d®, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Athens, Greece) and metronidazole in an unknown dose regimen for one month. After this treatment the stool was alternately normal or liquid. One month later, severe abdominal distension was developed and the animal was admitted to a different veterinary clinic. At this point hypoalbuminaemia and ascites were present. Symptomatic treatment (diuretic, unknown substance and dose regimen) resulted in improvement of clinical signs. One month later ascites was once more present and the dog was presented to a different clinician who recommended the consumption of codfish oil thrice a week. However, the appearance of the faeces continued to be soft and unformed, without deterioration in mood or appetite. For three weeks prior to admission in the CAC, the dog had ascites, poor body condition and diarrhea.

Physical examination revealed a poor body condition (BCS 1.5/5), ascites and diarrhea emitting a sour odour. Based on the CIBDAI scale (canine inflammatory bowel disease activity index), the animal’s enteropathy ranked as severe (CIBDAI: 9). The complete blood count (CBC) showed neutrophilic leucocytosis (12.200/ μl, reference range: 3.000-8.000/μl). Biochemistry revealed increased alkaline phosphatase activity (267 U/L, reference range: 32-149 U/L) and hypoalbuminaemia (1.5 g/dL, reference range: 2.9-4.0 g/dL). Moreover, vitamin Β12 and folic acid levels in serum were measured and results were within reference range. Abdominal radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities, ultrasonography showed abdominal fluid and the thickness of the intestinal wall was within maximum normal range. According to abdominal fluid cytology, it was classified as transudate.

During a two-day hospitalisation period, 200 ml of abdominal fluid were removed, furosemide (1 mg/kg SID, per os) (Lasix® 40 mg tab, Sanofi-Αventis A.E.V.E., Αthens, Greece) and spironolactone (1 mg/kg BID, per os) (ALDACTONE® 25 mg tab, PFIZER HELLAS A.E., Athens, Greece), as well as intravenous heterogeneous albumin (HUMAN ALBUMIN® 200 g/l sol inf, Baxter Hellas Ε.P.Ε., Athens, Greece) were administered. The dog was hospitalised for observation for the possibility of anaphylactic reaction following albumin administration and a clinical diet for liver disease was offered. After the restoration of albumin levels at the lowest normal range, further diagnostic investigation was recommended and an exploratory laparotomy was performed, aiming at acquisition of intestinal and hepatic biopsy samples.

Aetiologic diagnosis based on histopathology results was severe lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic enteritis, enteric lymphangiectasia and vacuolar hepatopathy.

After the immediate postoperative hospitalisation period, the dog was treated with prednisolone in immunosuppressive doses (2 mg/kg SID, per os) (PREZOLON® 5 mg tab, TAKEDA HELLAS Α.Ε., Αthens, Greece), gastroprotectants such as ranitidine (2 mg/kg BID, per os) (EPADOREN® 75mg/5ml syr, DEMO A.B.E.E., Αthens, Greece), and sucralfate in standard dose regimen (1 ml/6kg BID, per os) (PEPTONORM® 1000 mg/5ml oral susp, Uni-Pharma Α.Ε., Αthens, Greece), B-complex vitamin nutritional supplement (0.2 mg/dog SID, per os) (NEUROBION® 100+200+0.2 mg tab, Merck A.E., Αthens, Greece), ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg SID, per os) (URSOFALK® 250 mg cap, Galenica A.Ε., Αthens, Greece), middle chain triglycerides’ MCT oil (2 mg/kg SID, per os) and clinical diet with reduced fat content (Hill’s Prescription Diet Canine i/d®, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Αthens, Greece).

One year later, the dog remains steadily in good condition.

> Case 2

A 4-year-old, male intact Rottweiler, 41.3 kg, fully vaccinated and incompletely dewormed, housed indoors, was admitted due to chronic intermittent diarrhoea for the previous six months. According to the history, the faeces were liquid, malodorous, increased in volume, without tenesmus and this symptom had been present for a year prior to admission. Throughout this time, symptomatic treatment had been administered, in order to manage Giardia spp., and then coccidiosis as well as IBD and EPI, according to the instructions given from private practitioners, with unknown medications and dosage regimens. However, diarrhea and weight loss, reduction of appetite and polyuria/ polydipsia (PU/PD) persisted and for that reason a clinical diet was administered (Hill’s Prescription Diet Canine i/d®, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Αthens, Greece) for a time period of 40 days prior to admission.

During physical examination, moderately poor body condition was noted (BCS 2/5), with 7% dehydration and abdominal distension during abdominal palpation. The rest of the physical examination was normal. Based on the CIBDAI scale, enteropathy in this case was classified as severe (CIBDAI: 9). CBC was normal, whereas serum biochemistry showed increased ALP activity (307 U/L, reference range: 32-149 U/L), and hypoalbuminaemia (1.8 gr/dL, reference range: 2.9-4 gr/dL). Urinalysis showed reduced urine SG (1026, reference range: >1030) and bilirubinuria (++). Furthermore, levels of serum vitamin Β12 were reduced (180 pg/ ml, reference range: >350 pg/ml). Diagnostic imaging (abdominal radiograph and ultrasound) revealed ascites. Abdominal fluid evaluation classified it as transudate. During gastroscopy (OLYMPUS, XP20) nothing abnormal was observed macroscopically in the oesophagus and stomach. Reaching the small intestine was not possible, due to inability of the endoscope to pass through the pyloric sphincter.

During physical examination, moderately poor body condition was noted (BCS 2/5), with 7% dehydration and abdominal distension during abdominal palpation. The rest of the physical examination was normal. Based on the CIBDAI scale, enteropathy in this case was classified as severe (CIBDAI: 9). CBC was normal, whereas serum biochemistry showed increased ALP activity (307 U/L, reference range: 32-149 U/L), and hypoalbuminaemia (1.8 gr/dL, reference range: 2.9-4 gr/dL). Urinalysis showed reduced urine SG (1026, reference range: >1030) and bilirubinuria (++). Furthermore, levels of serum vitamin Β12 were reduced (180 pg/ ml, reference range: >350 pg/ml). Diagnostic imaging (abdominal radiograph and ultrasound) revealed ascites. Abdominal fluid evaluation classified it as transudate. During gastroscopy (OLYMPUS, XP20) nothing abnormal was observed macroscopically in the oesophagus and stomach. Reaching the small intestine was not possible, due to inability of the endoscope to pass through the pyloric sphincter.

Based on history and physical examination findings, chronic PLE and ascites were diagnosed. Prednisolone was administered (1.5 mg/kg BID per os), as well as omeprazole (0.25 mg/ kg SID per os) (LOSEC® 20 mg cap, Astra Zeneca A.E., Αthens, Greece), MCT oil and electrolytes-prebiotics–absorptive substances (Diarsanyl Plus® 10ml/24ml, Ceva, Αthens, Greece), in combination with a clinical gastrointestinal support type diet (Hill’s Prescription Diet Canine i/d®), whereas ascites was managed with furosemide (3 mg/kg BID per os).

Based on history and physical examination findings, chronic PLE and ascites were diagnosed. Prednisolone was administered (1.5 mg/kg BID per os), as well as omeprazole (0.25 mg/ kg SID per os) (LOSEC® 20 mg cap, Astra Zeneca A.E., Αthens, Greece), MCT oil and electrolytes-prebiotics–absorptive substances (Diarsanyl Plus® 10ml/24ml, Ceva, Αthens, Greece), in combination with a clinical gastrointestinal support type diet (Hill’s Prescription Diet Canine i/d®), whereas ascites was managed with furosemide (3 mg/kg BID per os).

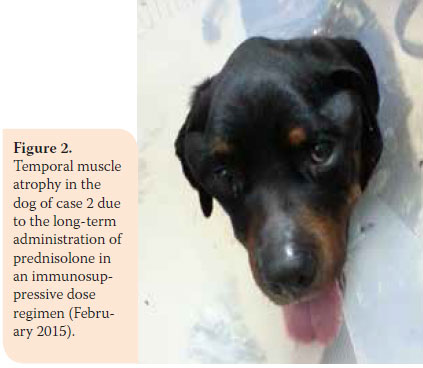

During re-examination one month later, the dog’s condition had improved. However, two months later, bright red blood was noted in the faeces and there was weight loss (36.5 kg). In the second re-examination there was poor body condition and increased ALT 124U/L (reference range: 18-62U/L), ALP activity was 1100U/L (reference range: 32-149U/L), and urinary SG was 1015 (reference range: >1030). A reduction in prednisolone dosage was recommended (0.75 mg/kg BID per os) and azathioprine was added to the dosage regimen (1.8 mg/kg BID per os) (AZATHIOPRINE® 50mg tab, Chemipharm Νtetsaves Ε.Ε., Athens, Greece). After one month, liquid to soft stool with blood spots was observed and the dog was readmitted. Hypoalbuminaemia was noted (2.2 g/dL, reference range: 2.9-4 g/ dL). One month later, the dog’s condition deteriorated. Physical examination revealed fever, skin lesions (figure 1), generalised muscular atrophy (figure 2) and weight loss. Biochemistry revealed increase in ALT (123 U/L, reference range: 18-62 U/L) and ALP activity (1,286 U/L, reference range: 32-149 U/L), and albumin levels were within lowest normal range (reference range: 2.9-4 g/dL). 10 days later, the dog was hospitalised with the intention of acquiring intestinal biopsies via laparotomy. During preliminary preoperative blood work reduced haematocrit was noted (32.5%, reference range: 37.1-55%) and hypoalbuminaemia (2.4 g/dl, reference range: 2.9-4 g/dL). For all of the above reasons a blood transfusion was administered, resulting in increase in haematocrit to 36.4% (reference range: 37.1-55%) and thus it was possible to proceed in obtaining intestinal biopsies. Postoperative laboratory diagnostics showed reduced albumin and total protein and the administration of heterogeneous albumin was selected (HUMAN ALBUMIN® 200 g/l sol inf, Baxter Hellas, Αthens, Greece). Τhe dog was hospitalised for observation for one day, in case there was anaphylactic response due to albumin administration and then it was discharged with the recommendation to continue treatment with prednisolone and azathioprine.

Aetiologic diagnosis according to histopathology results was lymphoplasmacytic enteritis and secondary lymphangiectasia.

Aetiologic diagnosis according to histopathology results was lymphoplasmacytic enteritis and secondary lymphangiectasia.

The dog was re-examined one month after the histopathology results became known. In consideration of the positive outcome, a gradual tapering of prednisolone dosage was decided leading to cessation of prednisolone. During re-evaluations every three months (lasting 18 months in total) the physical and laboratory outlook of the dog are both stable and stool has returned to normal, ascites has disappeared and body condition has improved (Figure 3).

> Discussion

The present study aims at describing the diagnostic procedures, therapeutic options and long-term prognosis in two dogs with PLE. This particular condition (PLE) emerges with frequency ranked from higher to lower in dog breeds, such as the Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier, Shar-pei, Yorkshire, Rottweiler, Basenji, Lundehund and English Springer Spaniel.5-7 Most cases with PLE coexist with IBD, lymphoma or lymphangiectasia.8 In the dogs of the present study, according to histopathology IBD (lymphoplasmacytic, eosinophilic enteritis) and secondary lymphangiectasia were present.

The causes for admitting these dogs included chronic intermittent diarrhea, originating from the small intestine, weight loss and ascites. In general, dogs with PLE have clinical signs in common with most ailments of the gastrointestinal tract. The most common signs include persistent or intermittent small intestinal diarrhea, weight loss, vomiting, ascites, hydrothorax, and subcutaneous oedema due to hypoproteinaemia.1,2

Diagnosing such cases can be challenging for clinicians. Through history and physical examination, a long list of differential diagnoses is formed including disorders of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal origin. Therefore, there is a need to perform laboratory diagnostics including CBC, a full routine biochemistry analysis and urinalysis.6 The most important laboratory findings that will guide the clinician toward the diagnosis of PLE are hypoalbuminaemia, hypoproteinaemia and hypocholesterolemia. 2 In these specific cases initial laboratory examinations did not offer any noteworthy findings. Therefore, further biochemistry diagnostics such as Β12 serum levels were performed. In general, findings including hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia and lymphopenia support the diagnosis of PLE, therefore it is important to measure these values in cases where PLE is suspected. 6,9,10 More specifically, lymphopenia occurs in cases of PLE due to lymphangiectasia,6 even though in the aforementioned cases this was not observed. Moreover, in complicated cases like the aforementioned ones, measuring bile acids could direct the clinician towards the underlying cause of protein loss. Increased bile acid levels combined with hypocholesterolemia and reduced BUN concentration cannot exclude PLE from the differential diagnosis, due to the fact that gastrointestinal tract disorders may cause an increase in bile acid serum levels.1,6 In such cases, differentiating a primary intestinal disorder from hepatopathies relies on histopathology or measuring levels of a1-protease inhibitor (a1-PI) in the faeces of suspected dogs. The a1-PI is a natural protease inhibitor (e.g. trypsin), which is of almost the same molecular weight as albumin. At any point in time when albumin loss occurs through the gastrointestinal tract, it occurs with simultaneous loss of a1-PI, which can be found intact in the faeces of afflicted dogs, therefore it can be used as a primary diagnostic marker for PLE.6,11 Unfortunately, due to technical difficulties, a1-PI was not measured in the faeces of these particular two cases. A case of a Beagle has been reported, in which diagnosis of PLE was possible based on a1-PI due to owner refusal of intestinal biopsies and the dog responded successfully to treatment.12

Regarding diagnostic imaging, radiographic evaluation of the abdomen does not reveal noteworthy findings in animals with PLE. On the other hand, abdominal ultrasonography is required, because it can be used as a guide in selecting the small intestinal biopsy technique (surgery or endoscopy). During ultrasonography, it is possible to reveal areas of increased echogenicity in the intestinal mucosa with severe furrowing, a finding characteristic of lymphangiectasia, as well as a generalised thickening of the small intestinal wall and mesenteric lymph node enlargement. Identification of localised or dissimilar varying lesions, which cannot be reached via endoscopy comprise sufficient evidence for a surgical approach.1,10 However, there are cases, when the particular diagnostic examination does not offer any intestinal findings, such as the above cases. Nonetheless, ultrasonography clearly revealed the presence of abdominal fluid in both dogs.

Confirmation of the diagnosis is obtained, based on histopathological findings from small intestinal biopsy samples. Biopsy samples can be obtained via endoscopy, or through exploratory laparotomy.2 Selecting the biopsy technique depends on several factors, some of which include available equipment and surgeon experience in performing a laparotomy or endoscopy. Some of the laparotomy advantages include the potential to observe the full length of the small intestine and to collect biopsy samples from all three segments. On the other hand, endoscopy offers access to the intestinal lumen, and biopsy samples can be selected from the intestinal mucosa from lesion areas only. The main advantage is that it is a less invasive method and that endoscopy can be performed in a much shorter amount of time. However, a main disadvantage of endoscopy is the failure of the endoscope to advance beyond the first segment of the duodenum.6,10 In case 2 an attempt was made to obtain biopsy samples via endoscopy, however crossing the pyloric canal was impossible, due to powerful sphincter contraction and severe distension of the stomach. Three months later, even though the dog’s condition was deteriorating, exploratory laparotomy was undertaken.

In both cases low levels of albumin in serum were found and intravenous administration of human albumin was decided. Administration of human albumin in both animals was performed, as described in the literature.13 In general, administration of human albumin should be selected, when all other ways of treatment have been attempted in cases with hypoalbuminemia.14 This conclusion stems from the fact that many side effects have been observed, which can be fatal for the patient, such as pulmonary oedema, renal failure and coagulation disorders, immediately following administration or even belated after 4-6 weeks. Other side effects that can be observed include lameness in the infused limb, lethargy, skin lesions due to vasculitis and fever.10,15 Τhe fact that the dogs of the present study did not develop an anaphylactic response can be due to immunosuppression due to long-term administration of prednisolone. It has been noted that levels of IgG antibodies against human albumin that are responsible for the type III hypersensitivity response, are reduced in severely debilitated animals compared to healthy ones. This is considered to be due to loss of IgG through the gastrointestinal tract, due to the main underlying disorder,14 which, in case of the present pair of dogs, was PLE.

Managing PLE cases is based on some important therapeutic guidelines. Initially, a proper diet should be offered, which should be continued throughout the dog’s life,2 just like the dogs in our study. More specifically, in both animals commercial clinical diets were offered with simultaneous administration of MCT oil (middle chain triglycerides). Alternatively, the diet can be replaced by a home-made diet, which should contain high quality protein originating from a single source (e.g. boiled chicken without the skin), carbohydrates (an ideal option is white boiled rice), limited amount of plant-based fibre and small amounts of fat, and it should be enriched with vitamins, minerals, calcium and phosphorus. The reduced amount of fat and, in particular, long-chain triglycerides, is a mainstay of treatment, because it reduces protein loss from the intestinal lumen. However, it is necessary to fulfil the dog’s caloric needs, therefore middle chain triglycerides should always be simultaneously offered, despite issues due to their taste.1,16 According to one publication, a dog with PLE due to lymphangiectasia was fed with a clinical diet only with satisfactory clinical results and no additional treatment was necessary.12 On the other hand, a clinical diet alone does not seem to be effective in dogs with severe clinical signs.16 In dogs with severe anorexia an effort for appetite stimulation is made (e.g. administration of cyproheptadine).2 In case the latter fails, dietary support is managed with enteral feeding, which contributes in restoring intestinal integrity.2

Prescription of immunosuppressants is of particular importance for the afflicted dogs’ clinical improvement. Initially, prednisolone is recommended to be offered in immunosuppressive dosage regimen for a duration of at least 4 weeks.2 Simultaneous administration of gastroprotectants is necessary when prednisolone is offered in immunosuppressive doses for long periods of time.2 In a previous study, reduction of fat content in the diet appears to result in improved response to treatment with reduced doses of prednisolone, reducing the probability of unwanted side-effects due to its catabolic effect.16 Prednisolone dose is gradually reduced after remission of clinical signs.2 When they are administered long-term this can result in undesirable side effects (e.g. iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism) and therefore coadministration of a second immunosuppressant (e.g. azathioprine) is advocated with simultaneous tapering of prednisolone dose.2,3 In case 2, after 3 months of treatment with prednisolone and omeprazole, azathioprine was added and prednisolone dose was tapered, due to the presence of undesirable side effects. Alternative to azathioprine, the following immunosuppressants can be used: cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, methotrexate and cyclosporine.16-17 According to a study, the combination of prednisolone-chlorambucil appears to increase albumin and body weight further and it manages a swifter clinical improvement, compared to the combination of prednisolone-azathioprine, as well as a correlation to an improved outcome.18 When cessation of treatment with prednisolone is deemed necessary, it is replaced by budesonide. Moreover, in animals with severe enteric malabsorption, dexamethasone is offered through the parenteral route.2

Administration of antibiotics is considered necessary in cases of PLE, due to concomitant SIBO. Antibiotics used in the clinical setting are metronidazole and tylosine.2

Due to severe hypoalbuminemia, cases of PLE present with ascites. In order to manage it, furosemide, spironolactone, or a combination of them is utilised.2 In a dog with PLE hypomagnesemia and secondary hypoparathyroidism were noted. Therefore, it is recommended to measure serum magnesium and, if that is reduced, it should be replenished. 9

An early indicator of PLE is the presence of perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCAs). Serology for pANCAs was found to be positive in dogs with PLE for 2.4 years prior to development of hypoalbuminaemia. Unfortunately, however, this test is unavailable in the clinical setting.11

Prognosis for dogs with PLE is guarded to poor. The CIBDAI score (canine inflammatory bowel disease activity index) which was calculated for the cases of the present study, comprises a prognostic factor for dogs with PLE.19-20 Response to treatment is unpredictable, and several cases go into clinical remission after months of treatment. After clinical improvement, some dogs remain in remission for years, whereas other dogs quickly develop hypoproteinaemia or thromboembolism. Moreover, other dogs fail to respond to treatment and then constantly deteriorate. Progressively and despite treatment, their condition deteriorates, until finally ending in death after generalised cachexia.10,16-17

> References

1. Milstein M, Sanford SE. Intestinal lymphangiectasia in a dog. Can Vet J 1977, 18: 127-130.

2. Rallis T. Disease of the small intestine. In: Gastroenterology of Dog and Cat. Rallis T (ed). 2nd edn. University Studio Press: Thessaloniki, 2006, pp. 145-189.

3. Birchard S, Sherding R. Disease of the small and large intestine. In: Saunders Manual of Small Animal Practice. Sherding R, Johnson S (eds). 3rd end. Rotoda: Thessaloniki, 2006, pp. 702-738.

4. Lecoindre P, Gaschen F, Monnet E. Disease of the small intestine. In: Canine and Feline Gastrenterology. Willard M (ed). Les Editions du Point Veterinaire: France, 2010, pp 246-316.

5. Simpson K, Jergens A. Pitfalls and Progress in the Diagnosis and Management of Canine Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, 41(2): 381-398.

6. Peterson PB, Willard MD. Protein-losing enteropathies. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2003, 33: 1061-1082.

7. Lane I, Miller E, Twedt D. Parenteral nutrition in the management of a dog with lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis and severe proteinlosing enteropathy. Can Vet J 1999, 40: 721-724.

8. Allenspach K. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology of the Canine and Feline Intestine. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, 41(2): 345-360.

9. Bush W, Kimmel S, Wosar M, Jackson M. Secondary hypoparathyroidism attributed to hypomagnesemia in a dog with protein-losing enteropathy. JAVMA 2001, 219: 1732-1734

10. Dossin O, Lavoue R. Protein-Losing Enteropathies in Dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, 41(2): 399-418.

11. Berghoff N, Steiner J. Laboratory Tests for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Canine and Feline Enteropathies. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, 41(2): 311-328.

12. Brooks T. Case study in canine intestinal lymphangiectasia. Can Vet J 2005, 46: 1138-1142.

13. Plumb D. Veterinary Drug Handbook. 7th Edition. PharmaVet: Stockholm, 2011, pp. 78-83.

14. Powell C, Thompson L, Murtaugh R. Type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in 2 critically ill dogs administered human serum albumin. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2013, 23: 598-604.

15. Vigano F, Perissinotto L, Bosco VR.Administration of 5% human serum albumin in critically ill small animal patients with hypoalbuminemia: 418 dogs and 170 cats (1994-2008). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2010, 20: 237-243.

16. Okanishi H, Yoshioka R, Kagawa Y, Watari T. The Clinical Efficacy of Dietary Fat Restriction in Treatment of Dogs with Intestinal Lymphangiectasia. J Vet Intern Med 2014, 28: 809-817.

17. Yuki M, Sugimoto N, Takahashi K, Otsuka H, Nishii N, Suzuki K, Yamagami T, Ito H. A Case of Protein-Losing Enteropathy Treated with Methotrexate in a Dog. J Vet Med Sci 2006, 68: 397-399.

18. Dandrieux J, Noble P, Scase T, Cripps P, German A. Comparison of a chlorambucil-prednisolone combination with an azathioprineprednisolone combination for treatment of chronic enteropathy with concurrent protein-losing enteropathy in dogs: 27 cases (2007–2010). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013, 242: 1705-1714.

19. Jergens A, Schreiner A, Frank D, Niyo Y, Ahrens F, Eckersall P, Benson T, Evans R. A Scoring Index for Disease Activity in Canine Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Vet Intern Med 2003, 17: 291-297.

20. Nakashima K, Hiyoshi S, Ohno K, Uchida K, Goto-Koshino Y, Maeda S, Mizutani N, Takeuchi A, TsuJimoto H. Prognostic factors in dogs with protein-losing enteropathy. Vet J 2015, 205: 28-32.