Ageliki Vorloka DVM, Vasilia Aggelou DVM, MSc, Kyros Chatzimisios DVM, MSc, Lysimachos G. Papazoglou DVM, PhD, MRCVS

Companion Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

MeSH keywords:

cat, dog, femoral head, femoral neck

Abstract

Anal sac disorders are commonly encountered in dogs, but they are less frequent in cats. They include impaction, anal sacculitis, abscessation and neoplasia. Indications for anal sac surgical removal (anal sacculectomy) include chronic recurring anal sacculitis, chronic recurring inflammation due to impaction, abscessation and perianal fistula, anal sac neoplasia and additionally, anal furunculosis when the anal sacs are involved. Τhere is an open and closed surgical technique for anal sacculectomy. Post-surgical complications are more commonly encountered after the open surgical technique. The complication rate is low and the prognosis following surgery is very good.

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Anal sac (AS) disorders are more commonly encountered in dogs and are less frequent in cats. Twelve percent of canine population and small breeds are particularly affected (Duijkeren 1995, Barnes & Marretta 2014, Charlesworth 2014). In a recent study, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Labrador Retrievers or Labrador crossbreeds had statistically significant predisposition to AS inflammation that required AS surgical removal (Charlesworth 2014). The AS disorders include impaction, that can occur bilaterally (Figure 1), anal sacculitis, which may be unilateral or bilateral, AS abscessation which is unilateral (Figure 2), and adenocarcinoma, which is the most common AS neoplasia, that can be unilateral or bilateral (Figure 3). Abscess rupture can lead to fistula formation (Figures 4 and 5) (Duijkeren 1995, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The exact aetiology of AS conditions remains unknown but several factors have been implicated including faecal consistency, physical activity, animal size, obesity, generalized seborrhoea, anal furunculosis, inflammatory bowel disease and impaction (MacPhail 2008, Barnes & Marretta 2014).

Surgical anatomy

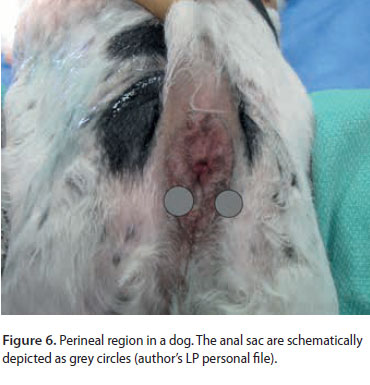

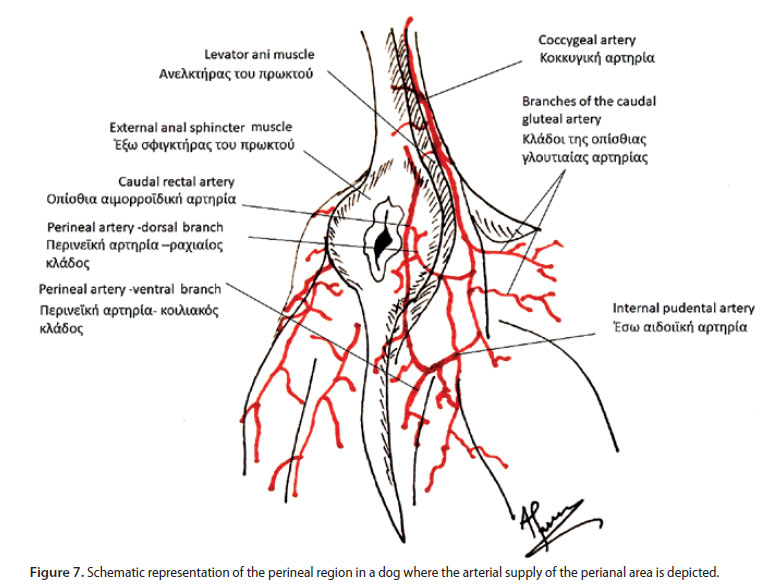

The AS are a pair of round cutaneous invaginations, located between the internal and external anal sphincter muscles, with a mean diameter of less than 1 cm (Figure 6) (MacPhail 2008, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The AS ducts, 5 mm in length and 2 mm in diameter, open between the dorsal and lateral parts of the inner cutaneous anal zone, and close to anocutaneous junction and intermediate zone in dogs, whereas in cats the AS ducts open on a pyramidal prominence 2.5 mm lateral to the anal orifice (MacPhail 2008, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). Τhe orifice of the AS ducts open at the level of the 4 and 8 o’clock position in the anocutaneous junction. The canine AS are mostly lined by stratified squamous epithelium with primarily apocrine glands and a few sebaceous glands, whereas in cats sebaceous glands are predominant. This difference in the epithelial layer might explain the reduced frequency of AS disorders in cats (MacPhail 2008, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The blood supply to the AS mostly includes branches of the caudal rectal, the perineal and the caudal gluteal artery (Figure 7) (Duijkeren 1995, Barnes & Marretta 2014).

The AS are a pair of round cutaneous invaginations, located between the internal and external anal sphincter muscles, with a mean diameter of less than 1 cm (Figure 6) (MacPhail 2008, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The AS ducts, 5 mm in length and 2 mm in diameter, open between the dorsal and lateral parts of the inner cutaneous anal zone, and close to anocutaneous junction and intermediate zone in dogs, whereas in cats the AS ducts open on a pyramidal prominence 2.5 mm lateral to the anal orifice (MacPhail 2008, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). Τhe orifice of the AS ducts open at the level of the 4 and 8 o’clock position in the anocutaneous junction. The canine AS are mostly lined by stratified squamous epithelium with primarily apocrine glands and a few sebaceous glands, whereas in cats sebaceous glands are predominant. This difference in the epithelial layer might explain the reduced frequency of AS disorders in cats (MacPhail 2008, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The blood supply to the AS mostly includes branches of the caudal rectal, the perineal and the caudal gluteal artery (Figure 7) (Duijkeren 1995, Barnes & Marretta 2014).

Indications for surgical removal and preoperative care

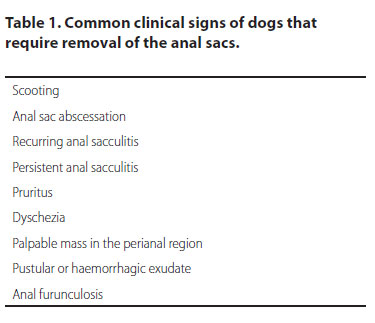

Anal sacculectomy is indicated in cases of chronic recurring anal sacculitis, chronic recurring inflammation due to impaction, abscessation and perianal fistula, AS adenocarcinoma and as an additional measure in cases of anal furunculosis when the AS are involved (Duijkeren 1995, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The clinical signs of dogs that require removal of the AS are summarized in Table 1 (Charlesworth 2014).Preoperative measures include manual emptying of the AS contents by digital pressure, infusion of antibiotic and glucocorticoid solutions into the AS via catheterization of the anal ducts and aggressive medical treatment, including systemic antibiotics, hot packs on the area for oedema resolution and thorough hygiene (Barnes & Marretta 2014). The aim of medical treatment is to manage the inflammation and to minimize potential complications. In cases of inflammatory disorders of the AS, bilateral sac removal is recommended (Duijkeren 1995, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014).

Anal sacculectomy is indicated in cases of chronic recurring anal sacculitis, chronic recurring inflammation due to impaction, abscessation and perianal fistula, AS adenocarcinoma and as an additional measure in cases of anal furunculosis when the AS are involved (Duijkeren 1995, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). The clinical signs of dogs that require removal of the AS are summarized in Table 1 (Charlesworth 2014).Preoperative measures include manual emptying of the AS contents by digital pressure, infusion of antibiotic and glucocorticoid solutions into the AS via catheterization of the anal ducts and aggressive medical treatment, including systemic antibiotics, hot packs on the area for oedema resolution and thorough hygiene (Barnes & Marretta 2014). The aim of medical treatment is to manage the inflammation and to minimize potential complications. In cases of inflammatory disorders of the AS, bilateral sac removal is recommended (Duijkeren 1995, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014).

Apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignant neoplasm, which affects older dogs, mostly Cocker spaniels, and which occurs with or without perianal swelling, tenesmus, constipation, hypercalcaemia related to paraneoplastic hyperthyroidism, polyuria and polydipsia. The AS can be unilaterally or bilaterally affected, and AS enlargement can often be diagnosed accidentally during a routine examination. Adenocarcinomas usually metastasize to the internal iliac lymph nodes and to the lungs (Polton & Brearley 2007). The survival time following anal sacculectomy ranges between 17-41 months (Potanas et al. 2015, Skorupski et al. 2018). The combination of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy can increase the median survival time (Bennett et al. 2002).

Surgical technique - general principles

Both open and closed techniques are recommended for anal sacculectomy; open technique requires a direct incision on the anal sac and duct and closed technique includes dissection around the intact AS or dissection following a Foley catheter placement into the duct (Barnes & Marretta 2014, Baines & Aronson 2018). AS adenocarcinoma is always removed using the closed technique. The open technique is simple and quick to perform, but because of the possible contamination of the surgical site, it may lead to increased postoperative infection. This is the reason why many surgeons prefer the closed technique in cases of anal sacculitis (Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014). Haemorrhage caused by surgical dissection of the sac either by open or closed technique can be managed by digital pressure or by electrocautery. Blind clamping of bleeding tissues by haemostats can result in trauma to the rectal nerve and it should therefore be avoided (Evans 2013). The incised anal sac can be recognized by its grey colour and shiny appearance. Regardless of the selected technique, trauma to the external anal sphincter and the caudal rectal artery and rectal nerve should be avoided. Surgical dissection and excision of the AS can be performed by scissors, scalpel or electrocautery. The authors prefer dissection and excision of the AS by electrocautery, because this technique results in less haemorrhage and reduction of surgical time. Surgical removal of the AS can also be performed by carbon dioxide laser, which is advantageous compared to the other techniques because of reduced haemorrhage, less pain, reduced oedema and decreased rate of postoperative infection (Evans 2013, Baines & Aronson 2018). Perioperative antimicrobials are also recommended, as the procedure is considered to be contaminated. At the time of surgery, the rectum is emptied and a tampon with antiseptic is placed in the anus and rectum to protect the surgical site. The AS are evacuated, and antiseptic solution is infused in both cavities. The dog is placed in sternal recumbency with the hind limbs hanging over the edge of the table and the tail is tied over the dorsum and secured by medical tape. A towel roll is placed under the caudal half of the dog for padding. The perianal area is then surgically prepped.

Open technique

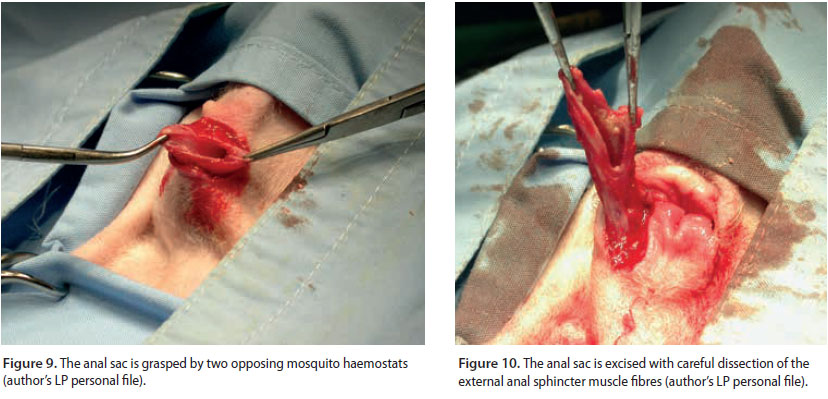

The open technique provides visualization of the secretory lining of the AS and therefore ensures complete removal of the AS and the anal duct (Baines & Aronson 2018). Disadvantages of this technique include the risk of damaging the external anal sphincter muscle and a higher postoperative infection rate due to contamination of surrounding tissue by the AS contents (Baines & Aronson 2018). During the open technique, a closed mosquito haemostat or grooved director is inserted through the duct and the AS is elevated towards the skin surface (Figure 8). With a no 10 scalpel blade in dogs and no 15 in cats, a longitudinal incision is made starting from the orifice of the duct opening towards the entire length of the duct and sac. With the aid of two mosquito haemostats, the AS mucosa is grasped by two opposing sites and the AS is excised by dissecting the muscular fibres of the anal sphincter with baby Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery (Figures 9, 10 and 11). After the AS and duct have been removed, the surgical site is lavaged with saline solution and the incision is closed in two layers, with a continuous synthetic monofilament 3/0 suture for the muscular and subcutaneous tissue and with 3/0 interrupted nylon sutures or with 4/0 intradermal continuous suture for the skin.

The open technique provides visualization of the secretory lining of the AS and therefore ensures complete removal of the AS and the anal duct (Baines & Aronson 2018). Disadvantages of this technique include the risk of damaging the external anal sphincter muscle and a higher postoperative infection rate due to contamination of surrounding tissue by the AS contents (Baines & Aronson 2018). During the open technique, a closed mosquito haemostat or grooved director is inserted through the duct and the AS is elevated towards the skin surface (Figure 8). With a no 10 scalpel blade in dogs and no 15 in cats, a longitudinal incision is made starting from the orifice of the duct opening towards the entire length of the duct and sac. With the aid of two mosquito haemostats, the AS mucosa is grasped by two opposing sites and the AS is excised by dissecting the muscular fibres of the anal sphincter with baby Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery (Figures 9, 10 and 11). After the AS and duct have been removed, the surgical site is lavaged with saline solution and the incision is closed in two layers, with a continuous synthetic monofilament 3/0 suture for the muscular and subcutaneous tissue and with 3/0 interrupted nylon sutures or with 4/0 intradermal continuous suture for the skin.

Closed technique

During the closed technique, the AS is removed intact with no incisions through the lumen, and the dissection is directed from the base of the AS toward the duct (Barnes & Marretta 2014, Baines & Aronson 2018). Placement of a mosquito haemostat inside the AS facilitates its identification and can guide the surgeon during dissection of surrounding tissues. A curved incision is made over the AS with the curve of the incision directed to the anus, parallel to the muscular fibres of the external sphincter muscle. The AS is carefully dissected away from surrounding tissues by removing the muscular fibres of the anal sphincter by curved baby Metzenbaum scissors or electrocautery. The dissection should be close to the AS to avoid trauma to the anal sphincter muscle and it is continued toward the duct. In cases of neoplasms, wider tissue dissection is performed to achieve local control. Damage to the caudal rectal artery can cause profuse bleeding and should therefore be avoided as it can obstruct visualization at the surgical site. The procedure is completed by ligating the segment of the duct closer to the anus by synthetic monofilament absorbable 4/0 suture. Lavage of the surgical site is followed by closure of the incision primarily with sutures similar to the open technique (Culp 2013, Evans 2013, Barnes & Marretta 2014, Ruffner et al. 2014, Baines & Aronson 2018). In cases of AS adenocarcinoma, the dissected tissues may include part of the rectum when infiltration by the mass is evident and 1 cm margins should be maintained around the resected tissues. Closure of the rectum incision is obtained with continuous or simple interrupted sutures with monofilament absorbable 3/0 or 4/0 suture. Closure of the subcutaneous tissue and the skin is performed as described previously (Culp 2013).

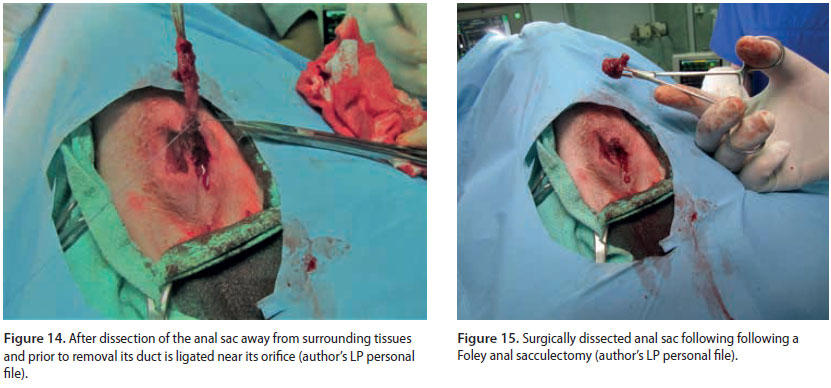

Closed technique with Foley catheter

This is a modified closed approach, in which a 6-French Foley catheter is placed into the AS through the duct (Figure 12) (Downs & Stampley 1998, Baines & Aronson 2018). The balloon is inflated with 1.5-3 ml of saline solution, resulting in visualization of the AS which is palpable under the skin. In cases when the catheter cannot be maintained within the AS lumen during the inflation, a suture is placed around the duct to keep the Foley inside the AS during balloon inflation. An incision is made on the skin over the dilated sac and the AS is dissected away from the surrounding tissues and muscular fibres of the sphincter as it was described in the closed technique. (Figure 13). After the dissection of the AS, the balloon is delated, and the catheter is removed. The AS is resected after ligation of the duct near the anus (Figures 14 and 15). The surgical site is lavaged and closed as described before (Downs & Stampley 1998, Baines & Aronson 2018).

Postsurgical treatment

An Elizabethan collar is placed on the animal for two weeks and broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered for 7-10 days, because the procedure is contaminated. Opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are administered to manage inflammation and postsurgical pain for 4-6 days. Cold packs are placed on the incision site for the first two days followed by hot packs 2-3 times daily for 10 minutes until suture removal.

Complications

Complications

Mild postoperative complications range from 3.2 to 32.5% (Hill & Smeak 2002, Charlesworth 2014). In a retrospective study of 95 dogs, it was found that the complication rate of anal sacculectomy was higher for the open technique compared to the closed technique (Hill & Smeak 2002). In another retrospective study, in which the closed technique was performed bilaterally, it was reported that post-surgical complications were more frequent for dogs weighing less than 15 kg (Charlesworth 2014). Short-term complications include scooting and inflammation of the perineal area, bruising, incisional exudate, incisional infection, seroma, wound dehiscence, tenesmus, diarrhoea, dyschezia and constipation (Hill & Smeak 2002, Charlesworth 2014, Baines & Aronson 2018). Defecation disorders have been observed in 3.2-14,5% of dogs that underwent bilateral closed anal sacculectomy, including reduced anal sphincter tone, soiling of the perineum with faeces after defecation, defaecation indoors and faecal incontinence. These complications resolved after a 10 day period and were attributed to mild trauma of the external sphincter during resection of muscular fibres at the time of AS dissection, or to neurapraxia related to inflammation and mild dyschezia (Hill & Smeak 2002, Evans 2013, Charlesworth 2014). Long-term complications were observed in 15% of dogs and included licking of the incision site, faecal incontinence, fistula formation and anal stricture (Figure 16) (Hill & Smeak 2002). Faecal incontinence persisting for more than 3-4 months is considered irreversible and usually results from extensive trauma to the sphincter or bilateral damage to the rectal nerve (Evans 2013, Baines & Aronson 2018). Fistula formation is caused by the incomplete removal of the AS, which usually occurs with the open technique, resulting in epithelial remnants in the surgical site. This complication can be managed by thorough surgical exploration of the fistula and resection of all diseased tissues. In general, the post-surgical complication rate of anal sacculectomy is relatively low, resulting in excellent prognosis (Evans 2013).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Baines S, Aronson L (2018) Rectum, anus and perineum. In: S. Johnston & K. Tobias, eds. Veterinary Surgery Small Animal. 2nd ed. Elsevier, St Louis, pp. 1783–1827.

- Barnes R, Marretta S (2014) Anal sac disease and removal. In: M. Bojrab, ed. Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery. 5th ed. Teton New Media, Jackson, pp. 306–309.

- Bennett PF, DeNicola DB, Bonney P et al. (2002) Canine Anal Sac Adenocarcinomas: Clinical Presentation and Response to Therapy. J Vet Intern Med 16, 100–104.

- Charlesworth TM (2014) Risk factors for postoperative complications following bilateral closed anal sacculectomy in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 55, 350–354.

- Culp W (2013) Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. In: E. Monnet, ed. Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, pp. 399–405.

- Downs M, Stampley A (1998) Use of a Foley catheter to facilitate anal sac removal in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 34, 395–397.

- Duijkeren E (1995) Disease conditions of canine anal sacs. J Small Anim Pract 36, 12–16.

- Evans H (2013) The digestive apparatus and abdomen. In: H. Evans & A. De Lahunta, eds. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. 5th ed. Elsevier, St Louis, pp. 281–337.

- Hill LN, Smeak DD (2002) Open versus closed bilateral anal sacculectomy for treatment of non-neoplastic anal sac disease in dogs: 95 cases (1969-1994). J Am Vet Med Assoc 221, 662–665.

- MacPhail C (2008) Anal sacculectomy. Compend Contin Educ Vet 30, 530-535.

- Polton GA, Brearley MJ (2007) Clinical stage, therapy, and prognosis in canine anal sac gland carcinoma. J Vet Intern Med 21, 274–280.

- Potanas CP, Padgett S, Gamblin RM (2015) Surgical excision of anal sac apocrine gland adenocarcinomas with and without adjunctive chemotherapy in dogs: 42 cases (2005–2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc 246, 877–884.

- Ruffner E, Fancher M, Sherman C et al. (2014) Anal sacculectomy in cats. Clin Brief 12, 31–35.

- Skorupski KA, Alarcón CN, de Lorimier L-P et al. (2018) Outcome and clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical factors associated with prognosis for dogs with early-stage anal sac adenocarcinoma treated with surgery alone: 34 cases (2002–2013). J Am Vet Med Assoc 253, 84–91.

Corresponding author:

Lysimachos Papazoglou

e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.