Fousekis A. DVM, Private practitioner | Panagiotou A. DVM, Private practitioner | Konstantarou E. DVM, Private practitioner | Kokkinou E. A. DVM, Private practitioner | Rizos S. Student, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece | Filippitzi M. E. DVM, PhD, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece | Papadimitriou S. DVM, DDS, PhD, Professor, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

MeSH keywords:Dental case treatment, cat, dental equipment, primary research, dog

Abstract

Objective

The survey was conducted in order to investigate the frequency of dental cases, the level of available equipment, the type of cases, the therapeutic treatment, etc. in the daily practice of veterinary practices and clinics in Greece.

Materials and methods

A specially structured questionnaire related to the management of dental cases in a veterinary practice was used, which was available online on a popular website, exclusively for veterinarians. The main areas explored included questions on: general context, available equipment, pre-, intra- and post-operative dental case management.

Results

Two hundred and ninety-two (292) veterinarians of all ages, practicing in Greece, responded to the questionnaire between 16/1/22 and 13/10/22. One- third of the respondents indicated that they have complete dental equipment, while almost 60% indicated that they treat at least one to two dental cases per week. A significant majority exclusively choose general anesthesia for dental procedures and tracheal intubation when performing them. Half of the veterinarians choose the combined use of corticosteroids and antibiotics as a way of treating feline chronic gingivostomatitis; in contrast, two out of three veterinarians do not recommend the administration of antibiotics following teeth scaling if teeth extractions are not required. Finally, one in five veterinarians consider that more than 15% of their income comes from dental procedures.

Conclusions

The results of the questionnaire show that the approach to dental cases by the veterinarians who responded to the questionnaire is generally in line with the guidelines of the relevant global literature.

Ιntroduction

Oral cavity diseases cause intense pain in animals, local but also systemic infections (Harvey 2022), such as inflammation and fibrosis of the liver (Debowes et al. 1996), chronic kidney disease (O’Neill et al. 2013, Finch et al. 2016) and endocarditis (Glickman et al. 2009). Therefore, according to the World Society of Small Animal Veterinary Medicine (WSAVA) dental guidelines, dental diseases that are not adequately treated degrade the quality of life of companion animals (Niemiec et al. 2020).

The first study on veterinary dentistry in the international literature was published in 1889, while from the 1930s onwards, veterinary dentistry is an integral part of daily clinical practice.

During the 20th Dentistry in companion animal practices century, the majority of cases mainly involved teeth extractions and dental scaling, as well as treatment of abscesses and extensive infections (Eisner et al. 2013)..

In our country, veterinary dentistry appeared in the second half of the 1990s and until today it has developed significantly both in the university and in the private sector. Indeed, a significant number of papers related to subjects such as the selection and use of the necessary dental equipment, the treatment of feline chronic gingivostomatitis, canine periodontitis, the correct use of antibiotics and anaesthetic management have been published in reputable national and international journals, while many oral presentations and short communications have been presented at national and international conferences (Papadimitriou 2018).

The aim of this study was to collect information and for the first time record the practice level of dentistry in daily veterinary clinical practice, in Greece. In particular, it addresses issues such as the frequency and management of dental cases, the level of available equipment, the type of cases and the time allocated to them. It also discusses the education of veterinarians through the university and other institutions, and the communication between veterinarians and guardians of small animals. This study also enriches the literature on the development of veterinary dentistry in Greece in recent years, and also provides readers with information on the correct use of equipment and case management, regardless of the answers given in this primary survey.

Materials and methods

Structure and distribution of the questionnaire Data collection was carried out using a specially structured questionnaire, which included 23 questions. The 15 questions were closed-ended likert scale questions, two of which allowed the respondent to choose more than one response. In the remaining 8, each respondent could give their own answer, as long as they were not satisfied with the proposed answers.

The questionnaire was distributed via an online platform to an online group of a large number of veterinarians, who are practicing in Greece and are professionally active in companion animal medicine, between January and October 2022. All data were imported into a Microsoft Excel file, where they were processed. The data were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis and are presented in the tables below.

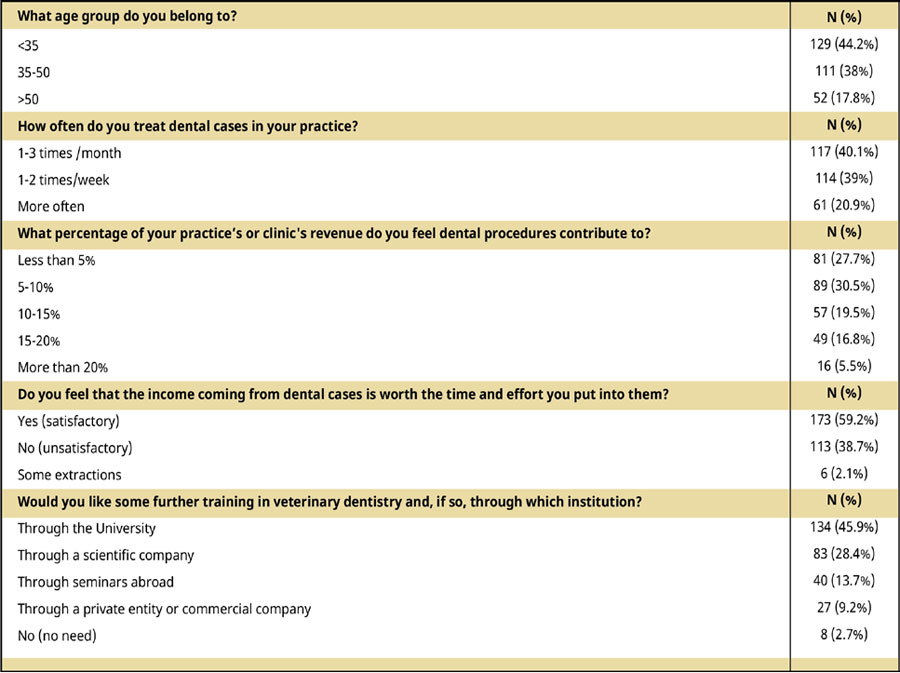

Table 1.

Results

The total number of respondents was 292, and all questions were answered by all participants. In all tables N represents the number of responding veterinarians who selected the corresponding answer.

In all the questions of Table 1, respondents were given the option to choose one of the suggested answers.

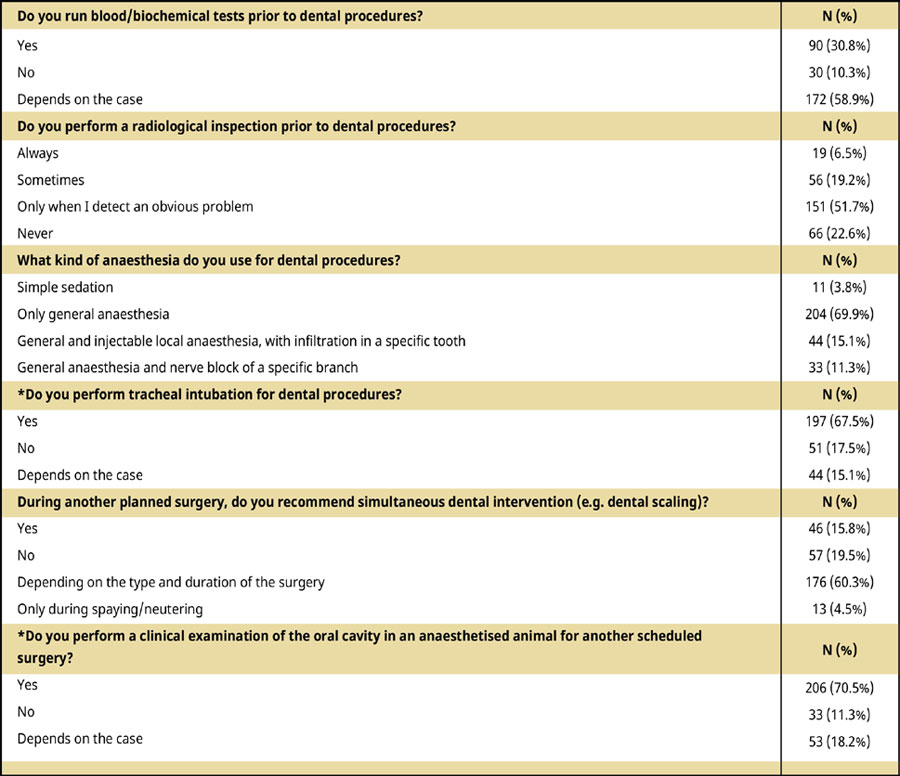

In all the questions of Table 2, respondents were given the option of choosing one answer. In the questions with an asterisk, participants were asked to make a comment if they selected the third option «depends on the case». In particular, 96.2% of veterinarians working in veterinary practices and clinics in Greece, regardless of age, use general anaesthesia for a dental surgery. The majority (67.5%) of veterinarians intubate the trachea when performing dental surgeries, while 15.1%. only on occasion. More specifically, some of the participating veterinarians (2.7%) always perform intubation in dogs and depending on the case in cats. Another portion of veterinarians (0.7%) only intubate during dental scaling. A small proportion of colleagues (1.4%) consider the severity of the dental case in their decision to intubate, and others are influenced by parameters such as age (0.7%) and breed (brachycephalic) (1%). However, because commenting on the same question was optional, 9.6% were content to choose «depends on the case» without justifying their choice. Finally, in a similar commentary question, 18.2% of the participating veterinarians performed a clinical examination of the oral cavity in an already anaesthetized animal for another scheduled surgery only if they noticed something alarming during the general clinical examination or during intubation of the animal. Indicative findings of concern were: halitosis, severe salivation, a facial deformity or a history of chewing difficulty or anorexia.

Table 2.

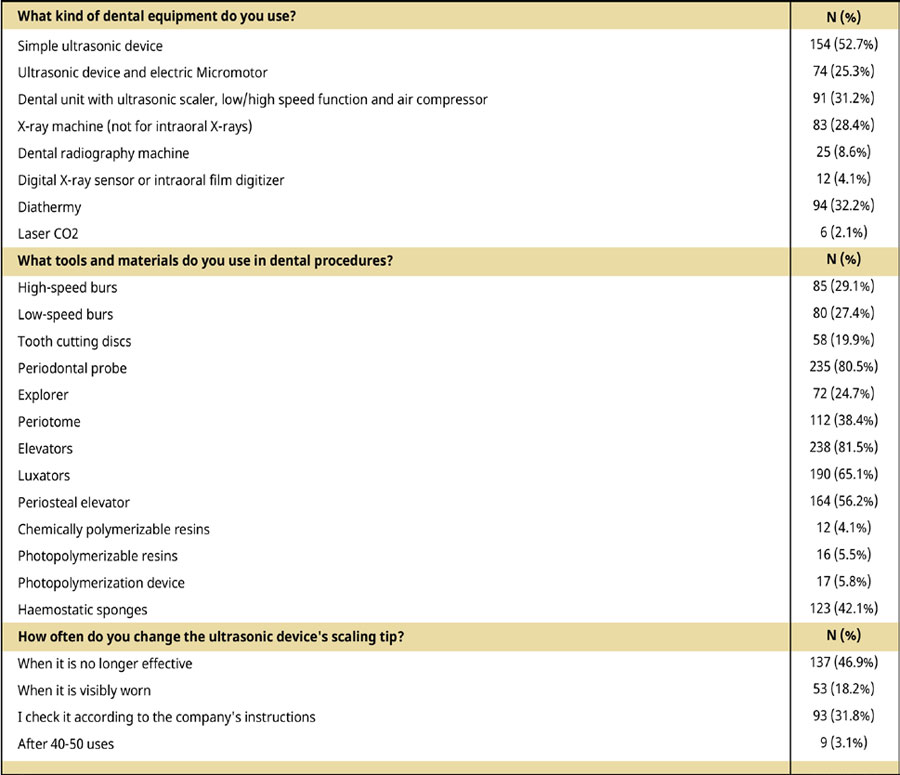

In the questions of Table 3, concerning the tools and equipment available to veterinarians in their workplace, respondents were allowed to select more than one answer, in contrast to the question concerning the frequency of changing the ultrasonic device’s scaling tip.

Table 3.

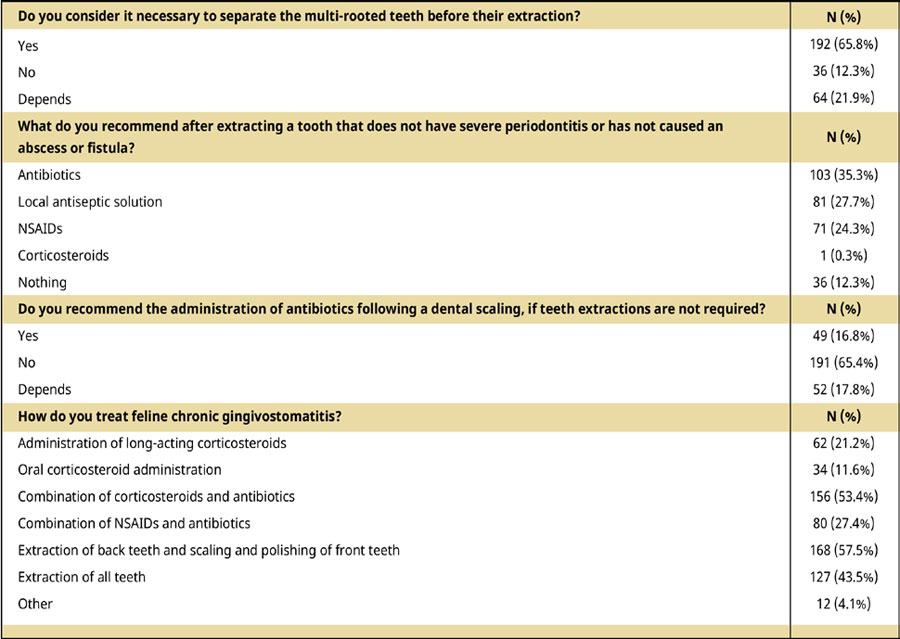

In all questions of Table 4, respondents were asked to choose one from the suggested answers, except for the question on feline chronic gingivostomatitis. The latter was given 77 different combinations of the suggested answers, and also a 4.1% went into further analysis of the options by talking about the chronological order of feline chronic gingivostomatitis management actions. 80.8% would attempt dental extraction at least of the premolars and moral teeth. Also, about 1% administered cyclosporine as an alternative response and local antiseptic solutions as adjunctive treatment, while 0.7% raised the owner’s wherewithal as another factor determining the approach to such cases.

Almost all of the respondents who occasionally perform separation of multi-rooted teeth (21.9%), consider that the degree of periodontal tissue damage and mobility determine the necessity of multi-rooted tooth separation.

A 17.8% of the surveyed veterinarians choose to administer antibiotics on a case-by-case basis after a dental scaling, which is not accompanied by an extraction. More specifically, 4.1% of respondents identified the progression of periodontal disease as an important parameter that would determine whether or not to give antibiotics at a dental scaling, while about 1% indicated that they choose to give antibiotics in cases where extensive bleeding is found.

Table 4.

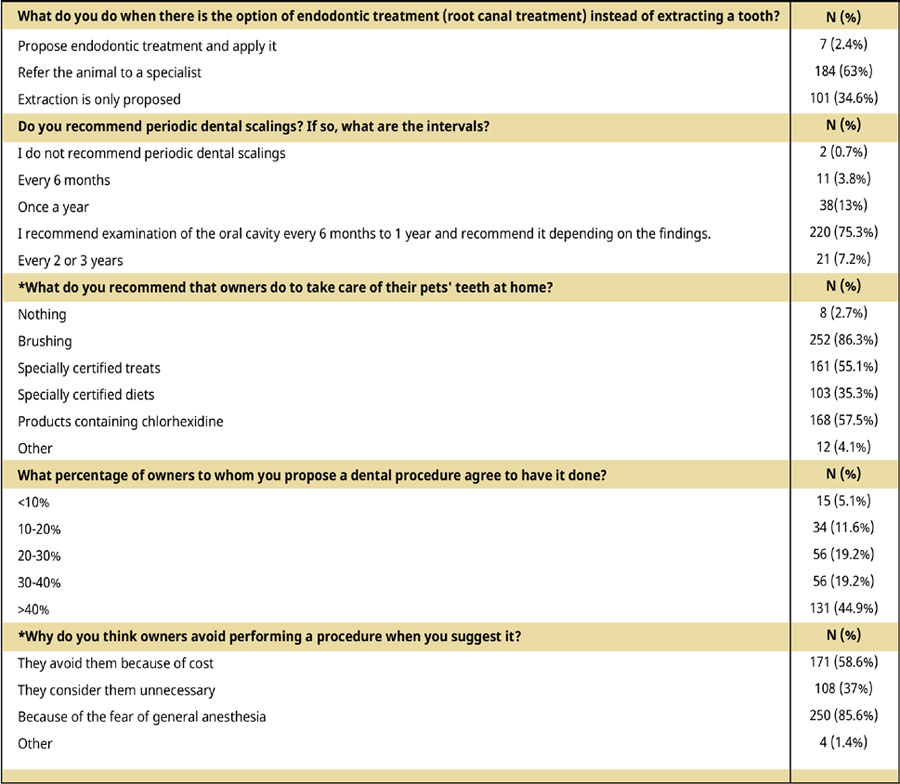

In all questions of Table 5, respondents were given the option of choosing one answer from the suggested ones, except for the questions with an asterisk. The results indicate that most veterinarians who suggest something different (4.1%) from the suggested answers regarding the care of pets’ teeth at home, recommend powdered food supplements that delay tartar deposition. Finally, a small group of veterinarians (1%) cite inadequate information for owners on dental problems and interventions as the main reason why an owner avoids performing a dental procedure on their pet.

Table 5.

Discussion

In companion animals, diseases of the oral cavity and teeth are a frequent challenge for veterinarians in daily clinical practice. In fact, 90% of dogs as young as one year old already suffer from periodon- tal disease. In addition, 10% of dogs are presented with teeth fractures with pulp exposure and up to 70% of cats show teeth resorptions (Niemiec et al.2020). Justifiably, therefore, 59.9% of the participating veterinarians in this study treat dental cases at least once or twice a week. In an equivalent survey conducted in Sweden in 2020 the results were similar, approximately six out of ten veterinarians treated dental cases with high frequency (Enlund et al. 2020). Also, veterinarians working in North American clinics ranked oral cavity examination as the 14 most frequently performed skill in clinical practice and the 8th most important skill that new graduates are expected to perform (Anderson et al. 2017). In a questionnaire addressed to UK students in their final year of studies, 99.5% responded that th dentistry is one of the important specialties for the clinical veterinarian (Perry 2014). It is very encouraging that more than two out of ten respondents, regardless of age, claim that at least 15% of their income comes from dental procedures. In addition, two out of three veterinarians whose dental procedures’ income makes up more than 15% of their total practice income, feel that these earnings commensurate with the time they invest. Almost all participants are interested in further training in veterinary dentistry. More than one in three wish to pursue this education through university activities, which testifies to the rising trend in the development of veterinary dentistry in Greece. Although the opportunities offered in the field of education are not the same in all countries, access to reliable websites with educational content is becoming increasingly easy. Indeed, the WSAVA (World Small Animal Veterinary Association) guidelines offer a very comprehensive overview of the dentistry specialty. Veterinary dental societies (European Veterinary Dental Society, Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry, British Veterinary Dental Association) also offer the possibility of further training in veterinary dentistry, while the two Colleges of Veterinary Dentistry (European Veterinary Dental College and American Veterinary Dental College) offer the pos- sibility for a relatively small number of veterinari- ans to train for three years and, after passing the examinations, to obtain the title of specialist in veterinary dentistry. It is worth noting that in a survey of 28 universities in 24 European countries in 2010, only a few universities in Europe provided a satisfactory training programme in veterinary dentistry, including the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. In fact, a 14% of the participants in the above survey stated that veterinary dentistry was not taught at all and a further 33% stated that dentistry was not part of the compulsory core courses (Gawor & Niemiec 2021). Regarding the UK, a number of final year students reported that dentistry was often not included in the examination syllabus (Perry 2014). Subsequently, according to the results of the present study, 58.9% of the respondents choose to per- form a preoperative haematological and biochemical screening of their patient, depending on the findings of the general clinical examination. Based on a study of 101 dogs over 7 years of age, almost 30% of animals undergoing preoperative screening were diagnosed with a systemic disease (Joubert 2007). Regarding radiographs of the teeth and maxilla/mandible, 51.7% of respondents choose to perform a radiographic examination only when they detect an obvious problem during the clinical examination of the oral cavity, while 22.6% never perform a radiographic examination. Not performing an imaging examination of teeth carries risks of incomplete or incorrect diagnosis. In fact, Eisner et al. (2013) observed that intraoral radiographs revealed clinically significant dental pathology in 27.8% of their dogs and 41.7% of their cats, in which no pathological findings were recorded during clinical oral examination. Often, intraoral radiography determines the management of the case (e.g. teeth resorptions in a cat), but also its prognosis (e.g. extent of a neoplasm and its effect on adjacent tissues) (Bannon 2013). Most likely reasons for not performing them are the lack of necessary equip- ment and objection by owners, mainly for financial reasons. The present study shows that 8.6% of the participants have a specialized radiographic machine for intraoral radiographs and about 5% use digital imaging systems for the radiographs (digital radiographic sensor or intraoral tile digitizer).

In terms of anaesthetic management, the WSA-VA and the vast majority of pet scientific societies worldwide are strongly opposed to performing dental procedures on unanesthetised animals (Niemiec et al. 2020). In fact, 96.2% of the participants in this study, regardless of their age, always perform dental procedures under general anaesthesia, ensuring not only the well-being of their patients, but also a more thorough examination and therefore a more accurate diagnosis and a more comprehensive and effective treatment (Roudebush et al. 2005). Moreover, general anaesthesia for another planned surgery, is an occasion for clinical inspection of the oral cavity (Gawor & Niemiec 2021). Three out of four respondents recognize and take advantage of this benefit. Of course, the necessity for general anaesthesia does not negate the general rule that the higher anaesthetic risk an animal is at according to the ASA scale, the higher the risk of complications during anaesthesia (Beckman 2013). Finally, both local and nerve block anaesthesia of areas of the oral cavity, as shown by the questionnaire responses, are mainly applied by young veterinarians. In the relevant literature it is recommended to intubate the animal regardless of the severity of the dental intervention and the type of anaesthesia, inhalation or injection, as long as water spray equipment is used, as intubation significantly reduces the risk of aspiration, providing greater safety for the patient (Beckman 2013). The majority (67.5% of veterinarians) agree with this practice, however, 83 of the 281 people who choose general anaesthesia do not consider intubation necessary, either because the tracheal tube makes dental manipulations more difficult or because it increases the cost of the procedure’s consumables. 60.3% of the respondents suggest that dental intervention should be performed at the same time as another planned surgery, depending on its type and duration. The surgeon’s experience, the reduction of multiple anaesthesias’ risk, the owner’s desire to save time and reduce costs play a decisive role in making the above decision. However, it is known that the oral cavity has an increased microbial load (Gorrel et al. 2013), therefore special care is required to avoid contamination when performing concurrent procedures in which aseptic conditions are required. Also, the increased risk of side effects should always be taken into account during prolongation of the general anaesthesia time (Gorrel et al. 2013).

It is encouraging that more than one in three owners are willing to carry out the suggested dental procedures, as more than half of the respondents to this questionnaire replied. The main reason for avoiding the proposed dental procedure is the owner’s fear of anaesthesia risk, which can, of course, be reduced by performing a full preoperative check-up. Another important factor in deciding whether to perform the dental procedure is its cost. Several owners, however, seem to understand the cost when the quality of work and the time required to perform a complete dental treatment are explained in detail.

Regarding dental equipment, when the veterinarian has the appropriate dental equipment for each case, their work is facilitated, and the likelihood of accidents is reduced (Gengler et al. 2013). Our study showed that almost half of the respondents seem to only use an ultrasonic device in clinical practice, while about one in three veterinarians have a dental unit with an ultrasonic device, low/ high speed handpiece and air compressor, thus being able to perform most dental work. According to Gawor and Niemiec (2021) it is preferable that the veterinarian acquires the ability to use the most appropriate equipment and then proceeds to purchase it. Continuing in the management and maintenance of the ultrasonic device, it is recommended to use handles and dental scaling tips from the same company, otherwise the risk of scaling tip distortion increases, which naturally leads to its disposal. 46.9% choose to replace the ultrasonic scaling tip when its effectiveness decreases, noting that it takes more effort and time to carry out the scaling process. The effectiveness of a dental scaling tip, however, largely depends on its correct use (Bazàn et al. 2020). In particular, the loss of the length of the scaling tip is proportional to the wear of the tool and naturally determines the replacement time of it. In fact, if the tip is damaged by one millimeter, its performance is reduced by 25% (Arabaci et al. 2013).

It is also noteworthy that more than eight out of ten veterinarians of all ages use a periodontal probe, as it is the most important tool for diagnosing the level of periodontal health and tooth adhesion (Abrahamsson & Soldini 2006). Through this survey it also appears that more than 50% of veterinarians have enough tools for teeth extraction, even Luxators being a relatively high-cost tool, thus taking care to ensure the integrity of both soft tissue and bone. There was no significant correlation between the age of the respondents and the use of more specialised tools or materials, except for resins, whose use is limited by older vets.

According to literature, teeth extraction, administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics and opioids, and maintenance of good oral hygiene are recommended as the treatment choice for feline chronic gingivostoma titis (FCGS) (Lee et al. 2022). In addition, the administration of corticosteroids should be avoided preoperatively and postoperatively so that they can be used and be effective in treatment-resistant cases (Winer et al. 2016). In contrast, the CO laser is used by very few veterinarians (2.1%) in the treatment of FCGS, mainly due to the high cost of the device (Lewis et al. 2007).

Regarding teeth extractions, the most frequent complication following extractions of multi-rooted teeth is root fracture because of the deviating curvature of the roots (Niemiec 2008). It is therefore justified that two out of three veterinarians perform separation of multi-rooted teeth before extraction. The majority seem to prefer the use of burs, as cutting discs can cause significant damage to adjacent tissues (Bellows 2019). No significant age variation in the use of cutting discs was observed in this study. In highly mobile teeth 21.9% of respondents do not perform root separation, however the risk of complications is not eliminated and therefore radiography of the area after each extraction is recommended (Moore & Niemiec 2014).

Regarding postoperative management of extractions, 35.3% of veterinarians routinely administer antibiotics. Current guidelines on the resistance of microorganisms to antibiotics recommend their administration sparingly, i.e. in cases with severe microbial infections of the oral cavity or in immunosuppressed animals (Gorrel et al. 2013).

It is worth mentioning that in cases where endodontic treatment is possible, 63% of the respondents suggest referring the case to a specialist, while 34.6% suggest direct extraction of the tooth. Endodontic treatment requires special equipment and experience with failure rate of only 6% (Verstraete et al. 2019), which is why in Greece a very small percentage (2.4%) performs it. However, the fact that a very high percentage of participants are informed about and recommend this procedure, is indicative of the interest in the specialty of dentistry.

Three out of four veterinarians do not recommend dental scaling at specific intervals but decide depending on the clinical condition of the patient, the willingness of the owner, but especially the health of the oral cavity. Scaling and polishing teeth on a more frequent basis than required by the clinical picture of the patient, carries anaesthesia risks, enamel erosion and thermal damage to the pulp (Gawor & Niemiec 2021). A survey conducted in the UK regarding the recommendations of veterinarians and nurses to owners to prevent oral cavity health in their dogs. 98% of the participants recommended tooth brushing, while 76% recommended dry food and 50% recommended specially certified treats (Fernandes et al. 2012). Educating owners on their pet’s oral hygiene seems to be particularly useful, as in addition to preventing periodontal disease, owners recognise and assess other oral cavity and dental problems in a timely manner and bring their pet to the vet (Enlund et al. 2020). It seems that in the U.S. owners are aware of the need for dental procedures, a study by the AAHA (American Animal Hospital Association) in 2003 showed that sufficient information was enough for them to accept to follow the advice of the veterinarian (Gawor & Niemiec, 2021). In contrast, in our country more than half of the veterinarians (55.1%) answered that less than 40% of the owners would perform a dental procedure on their animal, citing fear of general anaesthesia as the main reason, but also high costs or lack of information. Very important in improving this parameter is thorough information about the risks of an oral cavity disease for the local and general health of the animal and a complete preoperative check-up that provides safety during general anaesthesia.

Conclusion

Interest in the specialty of dentistry for both young and old veterinarians seems to be constantly increasing. Through the present primary research, it appears that a large proportion of veterinarians working in veterinary practices and pet clinics in Greece are informed about new developments in the specialty of dentistry, recognize its importance, have appropriate equipment, approach dental cases in an integrated manner, recognize the need for further education in the subject, and the provision of specialized services.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Corresponding author:

Athanasios Fousekis

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

References

- Abrahamsson I, Soldini C (2006) Probe penetration in periodontal and peri-implant tissues: An experimental study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Impl Res 17, 601-5.

- Anderson J, Goldstein G, Boudreaux K, Ilkiw J (2017) The State of Veterinary Dental Education in North America, Canada, and the Caribbean: A Descriptive Study. J Vet Med Educ 44, 358-363.

- Arabaci T, Cicek Y, Dilsiz A, Erdogan IY, Kose O, Kizildağ A (2013) Influence of tip wear of piezoelectric ultrasonic scalers on root surface roughness at different working parameters. A profilometric and Atomic Force Microscopy Study.Int J Dent Hyg 11, 69-74.

- Bannon KM (2013) Clinical Canine Dental Radiography. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 43, 507-532.

- Bazán MA, Carpintero Tepole V, Fuente EB, Drioli E, Ascanio G (2020) On the use of ultrasonic dental scaler tips as cleaning technique of microfiltration ceramic membranes. Epub 101:106035.

- Beckman B (2013) Anesthesia and Pain Management for Small Animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 43, 669-688.

- Bellows J (2019) Equipment, Instruments, and Materials for Operative Dentistry. In: Small Animal Dental Equipment, Materials, and Techniques. Wiley J& Sons Ltd, pp. 84.

- Debowes LJ, Mosier D, Logan E, Harvey CE, Lowry S, Richardson DC (1996) Association of periodontal disease and histologic lesions in multiple organs from 45 dogs. J Vet Dent 13, 57-60.

- Eisner ER (2013) Standard of Care in North American Small Animal Dental Service. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 43, 447-469.

- Enlund KB, Brunius C, Hanson J, Hagman R, Höglund OV, Gustås P and Pettersson A (2020) Dental home care in dogs - a questionnaire study among Swedish dog owners, veterinarians and veterinary nurses. BMC Veterinary Research.

- Enlund KB, Karlsson M, Brunius C, Hagman R, Höglund OV, Gustås P, Hanson J, Pettersson A (2020) Professional dental cleaning in dogs: clinical routines among Swedish veterinarians and veterinary nurses. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica.

- Fernandes NA, Borges APB, Pontes KCS, Reis ECC, Sepulveda R (2012) Prevalence of periodontal disease in dogs and owners’ level of awareness - a prospective clinical trial. Rev Ceres Viçosa 59.

- Finch NC, Syme HM and Elliott J (2016) Risk Factors for Development of Chronic Kidney. J Vet Intern Med 30, 602-10.

- Gawor J, Niemiec B (2021) Part III Dentistry in Daily Practice: What Every Veterinarian Should Know. In: The Veterinary Patient A Multidisciplinary Approach. Gawor J, Niemiec B ed. Wiley-Black- well, pp 261, 269-285.

- Gengler B (2013) Exodontics. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 43, 573-585.

- Glickman LT, Glickman NW, Moore GE, Goldstein GS, Lewis HB (2009) Evaluation of the risk of endocarditis and other cardiovas- cular events on the basis of the severity of periodontal disease in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 234, 486-94.

- Gorrel C, Andersson S, Verhaert L (2013) Anesthesia and Analgesia and Antibiotics and Antiseptics. In: Veterinary Dentistry for the GeneralPractitioner. Edinburgh, Saunders Elsevier, pp 15-35.

- Harvey CE (2022) The Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Systemic and Distant Organ Disease in Dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 52, 121-137.

- Joubert KE (2007) Pre-Anaesthetic Screening of Geriatric Dogs. J South Af Vet Assoc 78, 31-5.

- Lee DB, Arzi B, Kass PH, Verstraete FJM (2022) Radiographic outcome of root canal treatment in dogs: 281 teeth in 204 dogs (2001–2018). J Am Vet Med Assoc 260, 535-542.

- Lewis JR, Tsugawa AJ and Reiter AM (2007) Use of CO2 laser as an adjunctive treatment for caudal stomatitis in a cat. J Vet Dent 24, 240-9.

- Moore JI and Niemiec B (2014) Evaluation of extraction sites for evidence of retained tooth roots and periapical pathology. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 50, 77-82.

- Niemiec BA (2008) Extraction Techniques. Top Companion Anim Med 23, 97-105.

- Niemiec B, Gawor J, Nemec A, Clarke D, McLeod K, Tutt C, Gioso M, Steagall PV, Chandler M, Morgenegg G, Jouppi R, McLeod K (2020) World Small Animal Veterinary Association Global Dental Guidelines. J Small Anim Pract 61, 395-403.

- O’Neill DG, Elliott J, Church DB, McGreevy PD, Thomson PC and Brodbelt DC (2013) Chronic kidney disease in dogs in UK veterinary practices: prevalence, risk factors, and survival. J Vet Intern Med 27, 814-21.

- Perry R, Pavlica Z, Gawor J, Mestrinho L (2021) Part I General Considerations: How to Start Dentistry. In: The Veterinary Patient A Multidisciplinary Approach. Gawor J, Niemiec B ed. Wiley-Black- well, pp 29, 38, 14.

- Perry R (2014) Final Year Veterinary Students’ Attitudes towards Small Animal Dentistry: A Questionnaire-Based Survey. J Small Anim Pract 55, 457-64.

- Roudebush P, Logan E, and Hale FA (2005) Evidence-Based Veterinary Dentistry: A Systematic Review of Homecare for Prevention of Periodontal Disease in Dogs and Cats. J Vet Dent 22, 6-15.

- Trenter SC, Walmsley AD (2003) Ultrasonic dental scaler: associated hazards. J Clin Periodontol 30, 95-101.

- Verstraete FJM, Lommer JM, Arz B (2019) Endodontal Surgery. In: Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in Dogsand Cats.Elsevier, pp 217- 221.

- Winer JN, Arzi B, Verstraete FJM (2016) Therapeutic Management of Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Vet Sci 3, 54.

- Παπαδημητρίου Σ (2018). Άρθρο σύνταξης, Ιατρική Ζώων Συντροφιάς 7, 5-6.