Svoronou M. Veterinarian, MSc

Dourdas G. Veterinarian, CSAVP/Soft Tissue Surgery

Totta E. Veterinarian, CertAVP, PgCert VPS

Liapis I. Veterinarian, Cert. Ophthalmology

MeSH keywords: colorectal surgery, colostomy, surgical wound dehiscence

Abstract

Introduction: This report describes the use of a temporary end on colostomy to treat rectal perforation associated with rectocutaneous fistulas in a dog.

Description: The dog was presented with bite wounds in the perineal area. On physical examination an extensive cutaneous deficit in the perineal area and rectal perforation were identified. A primary repair of the rectal rupture was attempted and when dehiscence occurred, a temporary end on colostomy was performed to address fecal contamination of the wound. The wound was managed with tie over bandages until the formation of a healthy granulation bed, and reconstruction was performed with the use of a lateral caudal axial flap. Four months after surgery the perineal region had healed. The colostomy was closed and an endto-end anastomosis of the colon was performed. One year after the final surgery, the dog showed no fecal incontinence.

Discussion: Perineal wounds are challenging and the use of a temporary colostomy provides fecal diversion and facilitates healing.

Introduction

Perineal and perianal wounds present a challenge for the veterinarian due to the limited availability of skin for closure and the constant exposure to fecal contaminants and the associated risk of wound contamination (Bellah & Tail 2006, Skinner et al. 2016). In human medicine, temporary colostomy is frequently used for the management of perineal wounds, since it allows fecal diversion and contributes to uncomplicated wound healing. The is a scarcity of reports of colostomy that appeared in veterinary literature (Lewis et al. 1992, Tobias 1994, Hardie & Gilson 1997, Williams et al. 1999, Kumagai et al. 2003, Tsioli et al. 2009, Cinti & Pasagi 2019, Chandler et al. 2003), due to difficulties in postoperative care and owners’ non-acceptance (Tsioli et al. 2009). The objective of the present report was to describe the clinical findings, surgical treatment, and outcome of a dog that underwent temporary end-on colostomy for the treatment of rectal perforation associated with rectocutaneous fistulas.

Description

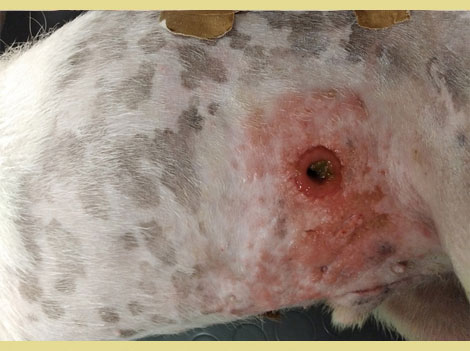

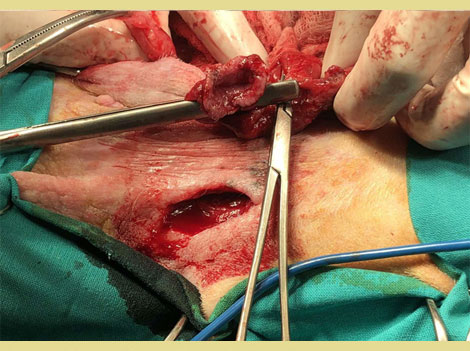

A 9-year-old intact male Jack Russel dog was presented, as an emergency, with a history of bite wounds in the perineal area. Clinical examination revealed an extensive cutaneous deficit at the base of the tail and the perianal region. Rectal perforation was also revealed. Luxation of the left elbow was also identified. The dog was hemodynamically stabilized with fluid therapy (Lactated Ringers at a dose of 10 ml kg-1 within 15 minutes) and analgesics [buprenorphine (Bupaq, Neocell, Greece)] at a dose of 0.02 mg kg-1 IM. [Cefazoline (Vifazolin, Vianex, Greece)] at a dose of 22 mg kg-1 IV, and [clindamycin (Dalacin, Pfizer, USA)] at a dose of 11 mg kg-1 IM were also administered. The dog was hospitalized and was scheduled for surgical exploration and wound reconstruction over the next few hours. Under general gas anesthesia, the wounds were debrided, the rectal perforations were closed with simple interrupted sutures (PDS 3/0, Ethicon, USA) and samples were taken for culture and sensitivity tests. The perineal wound was treated as an open wound with a wet-to-dry bandage that was changed daily (Figure 1). Closed reduction of the elbow luxation was performed and a spica splint was placed on the forelimb for 14 days. Postoperatively antibiotic administration was continued BID, and also meloxicam (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim, Spain) (0.1 mg kg-1 SC, SID) and buprenorphine (0.02 mg kg-1 IM TID) were given. Three days later dehiscence of the rectal wall and contamination of the perineal wound with feces was noted (Figure 2). A temporary colostomy was recommended as a treatment option. Anemia was identified prior to surgery [Hematocrit 22,3% (37.3-61.7)], the administration of meloxicam was discontinued and the dog received a transfusion of packed red blood cells (10ml kg-1). Based on the results of the culture (Escherichia Coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Proteus mirabilis) and sensitivity test, enrofloxacin (Baytril, Bayer, Germany) at a dose of 5 mg kg-1 SC, SID was administered. The dog was premedicated with a combination of Fentanyl (Fentanyl, Janssen, FAMAR, Greece) (2 μg kg-1 IV) and midazolam (Dormicum, Roche Pharma, Germany) (0.2 mg kg-1 IV). Propofol (Propofol MCT/LCT/Fresenius 1%, Fresenius Kabi, Austria) “to effect” was administered for anesthetic induction, and isoflurane (Iso-Vet, Piramal Healthcare, UK) in 100% oxygen for maintenance of anesthesia. Fentanyl was also administered at a constant rate infusion (CRI) at 0.1μg kg-1 min-1.

Figure 1. Wet to dry bandage 9 (personal file of the author MS).

Figure 2. Dehiscence of the rectal perforation site

The dog was positioned in dorsal recumbency and both the ventral and left lateral abdominal wall were prepared for surgery. A midline laparotomy was performed and the descending colon was transected 7 cm cranial to the pelvic brim. Both colonic stumps were sutured with a simple continuous simple pattern (PDS 3/0, Ethicon, USA). A two cm circular incision was made on the skin of the left lateral abdominal wall, and a smaller circular incision on the abdominal musculature. The proximal colonic stump was exteriorized through the incision and the sutures were removed. The seromuscular layers of the colon were sutured to the abdominal muscles with simple interrupted sutures (PDS 3/0). The stoma was created by suturing the colon (full thickness) to the skin with a simple interrupted non-absorbable suture (Polyamide 4/0, Medipac, Greece). The midline laparotomy was closed routinely. The perineal wound and rectal perforations were debrided and closed with simple interrupted sutures (PDS 3/0). Recovery from anesthesia was uneventful, and the fentanyl CRI was continued for a few hours postoperatively. Α combination of buprenorphine at a dose of 0.02mg kg-1 IM, TID, and paracetamol (Apotel, Uni-Pharma, Greece) at a dose of 10 mg kg-1 IV, TID was administered. The perineal wound was lavaged daily under a small dose of propofol and a tie-over bandage with medical honey (L-Mesitran, Bioskin, Greece) was applied until the formation of a healthy granulation bed.

Postoperatively the stoma was managed by using colostomy bags designed for children (Coloplast, Denmark) and by colonic irrigation. Irrigation was performed once daily with 250 ml of warm water, and the stoma was left without a bag for 30 minutes, to allow for colonic evacuation. Then the bag was reapplied. During the first postoperative days leakage of watery feces between the skin and colostomy bag was observed, resulting in peristomal dermatitis (Figure 3). Colonic irrigation was consequently discontinued, and dermatitis was treated with local application of a steroid-antibiotic ointment (Fucidin H, Leo Pharma, Denmark) and a sealing paste (Coloplast) around the stoma during bag changes. A two-piece colostomy bag replaced the single-piece bag and a belt adjusted to the dog’s waist was also used to support and stabilize the colostomy bag (Figure 4). The bag was changed daily and the flange every 3-4 days, when it stopped adhering to the dog’s skin. No further leaks were reported after these changes.

Figure 3. Dermatitis around the stoma.

Figure 4. Flange and belt on the stoma.

Eighteen days post-operatively, a healthy granulation bed had formed on the perineal wound, and closure was scheduled. A lateral caudal axial pattern flap was created to cover the perineal skin defect. A dorsal midline incision was made over the tail, the skin was carefully dissected from the underlying tissues taking care to preserve the lateral caudal arteries and veins. The tail was then amputated. The skin of the tail was used to cover the perineal skin defect and to reconstruct the anus (simple interrupted sutures were used (Polyamide 3/0, Medipac, Greece). A closed suction drain was placed during reconstruction for three days (Figure 5). Eighty days postoperatively, the perineal wound had healed completely and the anal sphincter function was restored. Two anal masses (Figure 6) and unilateral testicular enlargement were identified on clinical examination. Cytology from the perianal masses could not differentiate between adenoma and adenocarcinoma, so resection of the masses and orchiectomy were performed. The histopathologic diagnosis was perianal adenomas that were completely excised. The final surgery was postponed to allow the rectal area to heal. After the rectal area had healed completely, four months after the initial surgery, the repair of the temporary colostomy was scheduled. The dog was premedicated by the administration of acetylpromazine (Acetylpromazine, Alfasan, Netherlands) at a dose of 0.02mg kg-1 IM and butorphanol (Dolorex, MSD, USA) at a dose of 0.2mg kg-1 IM. Anesthesia was induced and maintained as described above. A midline laparotomy was performed and following a circular incision around the stoma the descending colon was exteriorized and resection of the stoma from the abdominal wall was performed. The mobilized colon was closed temporarily with sutures and returned to the abdominal cavity (Figure 7). Debridement of the central and peripheral colonic stump and end-to-end anastomosis with single interrupted full-thickness sutures (PDS 3/0, Ethicon, USA) (Figure 8) was performed. The abdominal cavity was then closed routinely and the colostomy site was sutured in 3 layers (muscular wall, subcutaneous, and skin). The recovery of the dog was uneventful.

Figure 5. Post-operative appearance of the perineal area after closure with the axial flap.

Figure 6. Perianal masses

During the postoperative hospitalization, the dog presented persistent diarrhea and fecal incontinence, which was treated with metronidazole (Metrobactin, Dechra, UK) at a dose of 15mg kg-1 PO BID for 20 days and probiotics for one month (Fortiflora, Purina, USA) at a dose of 1g SID. The dog was discharged from the clinic five days after surgery and continued the treatment at home. Fecal incontinence decreased over time. One year after surgery, the dog defecates normally and no episodes of incontinence are observed.

Figure 7. Colon has been mobilized from the abdominal wall.

Figure 8. End to end colonic anastomosis.

Discussion

There are a few reports of rectal perforation in the veterinary literature. The most common causes of rectal perforation are trauma (pelvic fractures, bite wounds), neoplasia, lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and irradiation therapy (Anderson et al. 2002, Chandler et al. 2005, Fransson 2008, Hoffberg et al. 2016, Lee et al. 2021, Muir 1998, Schiller 1967, Weaver & Omamegbe 1981, Woolhead et al. 2020). In dogs, perforation of the rectum is usually extraperitoneal and occurs within 4 cm away from the anus (Lewis 1992). Treatment options include primary closure with sutures, colostomy, or temporary stenting to divert feces and minimize fecal contamination of the wound, or the use of muscle flaps or biomaterials (Riggs et al. 2018, Skinner 2016, Tobias 1999). Permanent or temporary colostomy is a surgical technique that is widely used in human medicine in the management of colonic, rectal, and anal conditions, rectal perforation included. In the present case, an attempt was initially made to manage the perineal wound and rectal rupture as less invasively as possible, so primary closure of the rectal wall and management of the perineal wounds with wet-to-dry bandages were performed. The use of autolytic debridement and moist wound healing would have reduced the time of open wound management until granulation tissue formation compared to the use of wet-to-dry bandages. Dehiscence of the rectal wall was observed 3 days after its reconstruction. The failure of the caudal rectum to heal could be explained by its relatively poor blood supply compared to other areas of the gastrointestinal tract, its bacterial load, and the lack of omentum (Riggs et al. 2018). When dehiscence of the rectum was observed, a temporary end-on colostomy was performed to assure the diversion of the feces away from the wound. The use of a rectal stent was not considered due to the patient’s temperament and the risk of obstruction, or incomplete diversion of the feces away from the wound. There are few colostomy reports in small animal medicine. Two types of ostomies exist, end-on and loop. End-on or transverse ostomies involve suturing the intestine directly to a stoma in the abdominal wall and leaving a blind end in the aboral portion of the intestinal tract. Loop ostomies involve suturing an open loop of intestine to the stoma in the body wall (Chandler 2005). The most common complications are prolapse of the intestine through the stoma and dermatitis around the stoma (Hardie & Gilson 1997). Rare complications include peritonitis, ileus, abdominal or subcutaneous abscesses, stomal necrosis, and spontaneous stomal closure. In human patients, loop colostomy prolapses more frequently compared to end-on colostomy (Corman 1998). In veterinary patients, no prolapse has been reported. Skin irritation is a result of the incontinence that is caused by the colostomy, and the constant contact of the skin with feces. Numerous methods have been used to achieve continence in human patients with colostomies, the most successful being colonic irrigation with enemas once daily (Sanada et al. 1992). Williams et al investigated the use of irrigation in dogs with colostomy. Even though incontinence was not completely resolved, they report a significant reduction in fecal production over a 24-hour period (Williams et al. 1999). Fecal collection bags that are used in human patients contribute significantly to minimizing peristomal dermatitis. The problem is that glues and adhesives designed for human skin adhere poorly to canine skin (Hardie & Gilson 1997). Moreover, the proximity of the flank fold to the site of the stoma makes the adhesion of the bag challenging. As a result, the use of colostomy bags has been unsuccessful in many veterinary reports (Cinti & Pasagi 2019, Hardie & Gilson 1997). In the case presented here, no prolapse of the stoma was observed, and colostomy bags were used to manage fecal incontinence. In order to minimize peristomal dermatitis and facilitate the management of the colostomy, colonic irrigation was implemented in the post-operative management, but was discontinued due to the constant production of watery feces that led to peristomal dermatitis. Colostomy bags were replaced by two-piece bags (separate flange and bag), and a colostomy belt and an adhesive paste were used to improve sealing around the stoma. These changes led to a reduction of skin irritation and facilitated colostomy management for the owners after the dog was discharged. The use of colostomy bags was successful in this case, in contrast to most previous reports.

Perineal skin defects present difficulties in management due to the lack of excessive skin in the area. In some cases, the scrotum can be used in male dogs following castration, or the dorsal vulvar skin in female dogs (Bellah & Tail 2006, Grigoropoulou et al. 2013). The tail skin as a flap (lateral caudal axial pattern flap) has also been described (Lee et al. 2021, Kokkinos et al. 2017, Saifzadeh et al. 2005) to cover defects both dorsally and ventrally to the anus. When the skin is flapped cranially, the appearance of hair growth is not completely cosmetic (Bellah & Tail 2006).

To cover the perineal skin defect, that extended dorsally and around the anus, a caudal lateral axial pattern flap was used. The skin reconstruction was performed after the formation of a healthy granulation bed on the wound. The reconstruction of the mucocutaneous junction of the anus was tension free and the healing of the area was completed without complications. To conclude, temporary end-on colostomy could be used as part of the management of perineal wounds in dogs associated with rectal perforation and rectocutaneous fistula formation when fecal contamination of the wound is an inhibiting factor in healing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson CR, McNiel EA, Gillette EL, Powers BE, LaRue SM (2002) Late complications of pelvic irradiation in 16 dogs Vet Radiol Ultrasound 43, 187-192.

- Bellah J R (2006) Tail and Perineal Wounds. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 36, 913-929.

- Chandler JC, Kudnig ST, Monnet E (2005) Use of laparoscopic-assisted jejunostomy for fecal diversion in the management of a rectocutaneous fistula in a dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 226, 746–751.

- Cinti F, Pasani G (2019) Temporary end-on colostomy as a treatment for anastomotic dehiscence after a transanal rectal pull-through procedure in a dog. Vet Surg 48, 897-901.

- Corman ML (1998) Intestinal stomas. In: Ed M L Corman ed. Colon and Rectal Surgery, 4th ed, Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia pp.1264-1319. Fransson BA (2008) Rectocutaneous fistulas.Compend Contin Educ Vet. 30, 224–227.

- Grigoropoulou VA, Prassinos NN, Papazoglou LG, Galatos AD, Pourlis AF (2013) Scrotal flap for closure of perineal skin defects in dogs. Vet Surg 42, 186-191.

- Hardie EM, Gilson SD (1997) Use of colostomy to manage rectal disease in dogs. Vet Surg 26, 270–274.

- Hoffberg JE, Koenigshof AM, Guiot LP (2016) Retrospective evaluation of concurrent intra-abdominal injuries in dogs with traumatic pelvic fractures: 83 cases (2008–2013). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 26, 288–294.

- Kokkinos P, Kouki M, Montzolis G, Savvas I, Delligiani A, Papazoglou LG (2017) Lateral axial pattern flap after tail amputation for coverage of a dorsal pelvic and perineal skin defect in a cat. Aust Vet Pract 47, 25-28.

- Kumagai D, Shimada T, Yamate J, Ohashi F (2003) Use of an incontinent end-on colostomy in a dog with annular rectal adenocarcinoma. J Small Anim Pract. 44, 363–366.

- Lee J, Kang J, Kim N, Heo S (2021) Rectal perforation associated with a pelvic fracture managed with lateral caudal axial pattern flap surgery using the tail to skin defect in a mixed-breed dog. J Vet Clin 38, 240-243.

- Lewis DD, Beale BS, Pechman RD, Ellison GW (1992) Rectal perforations associated with pelvic fractures and sacroiliac fracture-separations in four dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 28, 175–181.

- Muir P (1998) Rectal perforation associated with pelvic fracture in a cat. Vet Rec 142, 371–372.

- Riggs J, Ladlow JF, Owen LJ, Hall JL (2019) Novel application of internal obturator and semitendinosus muscle flaps for rectal wall repair or reinforcement. J Small Anim Pract 60, 191-197.

- Saifzadeh S, Hobbenaghi R, Noorabadi M (2005) Axial pattern flap based on the lateral caudal arteries of the tail in the dog: an experimental study. Vet Surg 34, 509–13.

- Sanada H, Kawashima K, Tsuda M, Yamaguchi A (1992) Natural evacuation versus irrigation. Ostomy Wound Management 38, 386-89.

- Schiller AG, Helper LC, Knecht CD (1967) Repair of rectocutaneous fistulas in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 150, 758-759.

- Skinner OT, Cuddy LC, Coisman JG, Covey JL, Ellison GW (2016) Temporary rectal stenting for management of severe perineal wounds in two dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 52, 385–391.

- Tobias KM (1994) Rectal perforation, rectocutaneous fistula formation, and enterocutaneous fistula formation after pelvic trauma in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 205, 1292–1296.

- Tsioli V, Papazoglou LG, Anagnostou T, Kouti V, Papadopoulou P. (2009) Use of a temporary incontinent end-on colostomy in a cat for the management of rectocutaneous fistulas associated with atresia ani. J Feline Med Surg 11, 1011–1014.

- Weaver AD, Omamegbe JO (1981) Surgical treatment of perineal hernia in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 22, 749-758.

- Williams FA, Bright, RM, Daniel GB, Hahn, KA, Patton SA (1999) The use of irrigation to control fecal incontinence in dogs with colostomies. Vet Surg 28, 348–354.

- Woolhead VL, Whittemore JC, Stewart SA (2020) Multicenter retrospective evaluation of ileocecocolic perforations associated with diagnostic lower gastrointestinal endoscopy in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 34, 684-690.

Corresponding author:

Svoronou Mirsini

e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.